Natalie Dormer on the Frighteningly Contemporary Themes in Amazon’s ‘Picnic At Hanging Rock’

Natalie Dormer probably has the best smirk in Hollywood. With a mischievous twist to her lips and a naughty glint in her eyes, she always looks like she’s tasting amusement. But as Hester Appleyard, the headmistress of a secluded Victorian girls’ school in the Australian Outback in Amazon’s Picnic at Hanging Rock, that knowing look morphs into a sinister scowl.

The six-hour miniseries draws from author Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel rather than director Peter Weir’s venerated 1975 film to flesh out the story of three students and their teacher who mysteriously disappear on a Valentine’s Day outing to the titular rock formation.

Ahead of the highly anticipated premiere, Dormer spoke with TVInsider.com about her character’s dodgy motivations and why Picnic at Hanging Rock remains relevant today.

Everything gets rebooted and remade these days, and in a way that ups the stakes. If you’re going to reimagine something it better be worth it. What convinced you this series was worth the risk and the scrutiny?

Natalie Dormer: It’s the writing. It’s the writing of the series. Beatrix Christian’s bible is the novel, Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock. And there are numerous examples of really good novels, really good stories or plays being made again and again. That’s when you know you have good source material, when it can be revisited and reinvented.

So, reading the novel, I realized how much subtext is there that Joan Lindsay refers to or nods at or hints at. You really can’t do justice in the length of a feature film. Peter Weir’s movie is so heralded and beloved, it really does what it does. And what we can do in six hours is explore storylines, ensemble characters, and really push in depth into people’s backstories and characterizations like you could never do in a two-hour movie. You really get to know who these people are and flesh out the community a lot more.

The short answer is, Bea Christian’s first three scripts were outstanding, and I didn’t have the baggage of Peter Weir on my shoulders, because I’d never seen [the film] at the time.

I’m exactly the opposite. I’ve seen the movie but never read the book.

Well, it was good for me because the source material was the book for our piece. So my first impression was Joan Lindsay. And then Bea very much carries the spirit of Joan Lindsay.

What were the things in the book that you wanted to see fleshed out more in the series?

Well, Hester’s journey would be the obvious, immediate answer, because Lindsay nods to the fact that this woman had an entirely different life in London, and she doesn’t really go into any detail as to what it was.

You know there was a husband, and you know that she might not necessarily have all the credentials that she refers herself as having in Australia. That’s the whole point of the colony. People literally went to the other side of the world and reinvented themselves. Bea took that and she ran with it, and I just thought it was delicious, the entire backstory—the ghosts that Appleyard is running from.

What did you find most compelling about your character, Hester Appleyard?

The thing I loved, which was delicious to play, was that this woman thinks she’s helping these girls.

Do you think she thinks that?

Yeah. No human being thinks they’re a monster or a tyrant. Name me a tyrant or a despot that thinks they’re a tyrant. The reason I took the job was because Larysa Kondracki wrote me such a beautiful letter that said, “the danger with Hester Appleyard is that she is perceived as a two-dimensional villain, and I need an actress that will bring the vulnerability to her.”

She had acted out of her own past motivations. As the six hours play, you understand that Hester was a victim herself. I don’t believe that just because bad things happen to a person it excuses their behavior, [but] she is a product of what happened to her in her past. She has assumed a structured environment that she can be this leader of this little fiefdom, contained in a community that she can rule in order to feel safe, to feel in control.

But these young girls are at the start of a new century. The industrial revolution’s about to happen. In 20-something years women are going to have the vote. So these young girls are the spirit of the future. Hester is trying to tutor them in a Victorian, outdated mode that she thinks will help them. She’s trying to teach the discipline and structure and elegance, when really the way to the 20th century is liberation, embracing of change. And change terrifies Hester.

I think one of the most notable things about the series is that the filmmakers behind this version are women telling a story about women. Do you think that changes the story? In what ways?

I don’t think it’s anything we aimed for. I just think by the nature of it, it shifts somewhat. But it’s not female exclusive. There are male characters on their own deeply personal journeys. Harrison Gilbertson is a case in point, and we had incredible male HODs like our DP Gary Phillip.

It was female-centric in storytelling, in front of and behind the camera, but it’s not female exclusive. At the end of the day we’re all just storytellers who want to tell a really good story. Any differences that there may or may not be—it’s not constructed, it just happens naturally. And I wouldn’t even be able to tell you—you might be able to comment on the more than I would. I just turn up and do my job and collaborate with women that I thought were incredible storytellers. We just did our job every day and had conversations. Whatever happens is organic. It’s an esoteric thing. I don’t think I could pinpoint it for you.

Although, I suppose Larysa [Kondracki], as our showrunner—I’m not speaking for her now, but she points out that she very definitely didn’t want full frontal female nudity. In fact, the only full frontal nudity you’ll see is male. So, in that way, I guess she just naturally takes the story out of the male gaze and it comes from a place of humanity.

The landscape of Australia was such a big part of the story. You filmed on location. So how did that enhance the experience?

It was extraordinary and I benefited from the fact that it was my first visit to Australia. So the sort of awe and shock of the majesty of the landscape and the sounds and the smells of the flora and fauna, and the heat—when I arrived it was sort of the end of summer. So that sort of hit me the way it does Hester Appleyard when she arrives. It’s a very alien landscape for a Londoner! [Laughs] I mean, it’s stunning. I adored Australia. It was sort of NAR—no acting required—in that regard. The way it hit me, it hit Hester.

So, the flip side of that is the very Victorian atmosphere of this cloistered girls’ school. There’s something so creepy about that kind of archaic, severe, female-only environment. Why do you think that is?

Well…it’s a completely different era in its technology. Life was much, much slower. You really are going to the other side of the world and contact with civilizations back in Europe—you kind of disappear, never to be heard of again. But what I find terrifying is what hasn’t changed. Young girls trying to shake off authority, their superiors who they don’t think understand their way of thought or the way they communicate with each other. Concepts of independence, financial and emotional, from men. I more startled by what is similar, to be perfectly honest.

This is a story about the end of the 19th century, it was written in the mid-20th century, and this new adaptation comes during the 21st century. What does Picnic at Hanging Rock have to offer a contemporary audience?

It’s the continued fight for liberation. I’m not just talking about the women here. I’m also talking about sexuality. Mike [Harrison Gilbertson] definitely has his own journey to do with his sexuality. We have issues with ethnicity. We couldn’t do justice to everything in six hours, but when I talk about liberation I don’t just mean female liberation.

In 1900, within the next 20 years women are fighting for the vote. When Joan Lindsay wrote this book it was the 60s—I don’t think you need a lecture on the kind of liberation that was happening in the 60s. And we find ourselves in a new chapter of liberation, particularly in the last handful of months.

I find it quirky that Joan Lindsay was so obsessed with time. Time can be irrelevant and not necessarily a linear thing. How apt that we’re looking at all these aspects of liberation and you could jump back and forth [in time] in comparing them. So it is a story for our time. It’s a story about the individual finding the truth within themselves. Hester looks deep inside at the truth of herself and it’s a pretty horrific reckoning when she does.

Picnic at Hanging Rock, streaming on Amazon

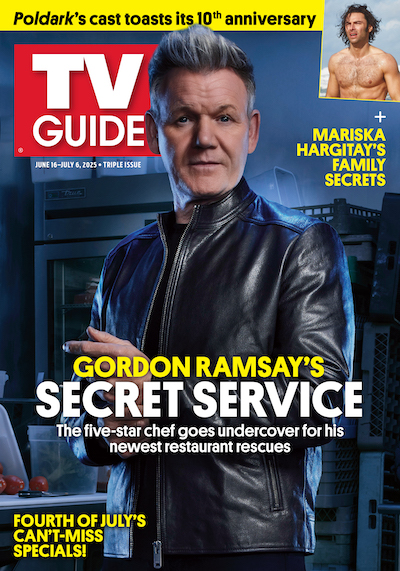

From TV Guide Magazine

Behind the Scenes With Gordon Ramsay: 20 Years of Cooking Up TV Hits

The celebrity chef reflects on redefining culinary television and his fiery journey Hell’s Kitchen to Secret Service. Read the story now on TV Insider.