David Letterman: The Outsider Who Was King

A Conan writer named Andrés du Bouchet recently went on a Twitter rant about the rise of “Prom King comedy,” criticizing late night hosts for their reliance on celebrity gags, “hashtag wars,” and lip-syncing, and accused the masses of letting “the popular kids appropriate the very art form that helped you deal.”

The tirade brought headlines and a reprimand from Conan O’Brien. But it was also a reminder that when David Letterman broadcasts his final Late Show on May 20th, late night television will lose something important: its anti-Prom King.

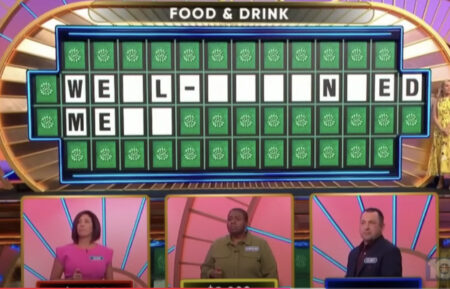

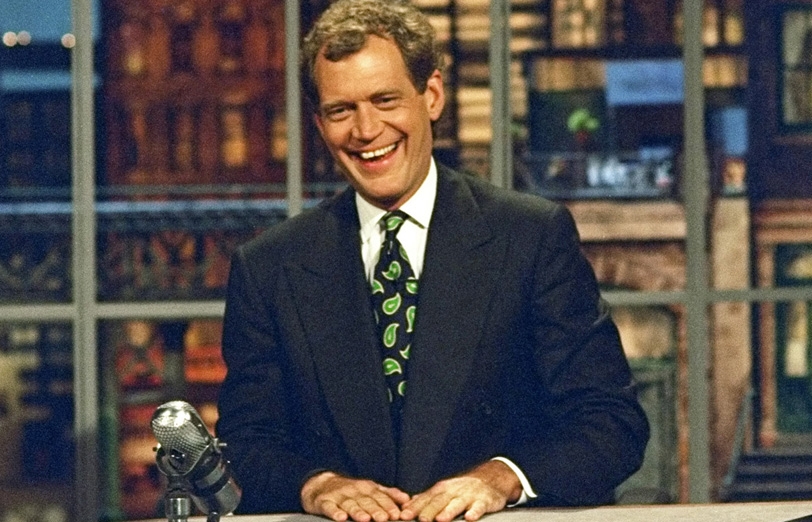

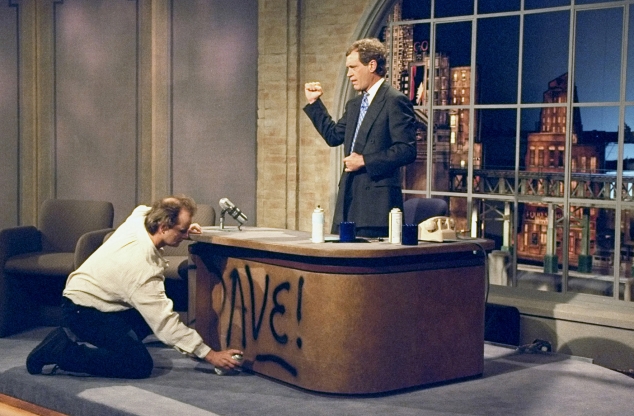

During the Late Night With David Letterman era on NBC, as well as the decades he spent as ringmaster of CBS’s Late Show, Letterman – who will be honored in a CBS tribute special that airs tonight — always positioned himself as an outsider, a gap-toothed rube from Indiana who somehow stupid-human-tricked his way into a gig as the host of his own show. That’s not true, of course. Letterman spent years as a comedian, actor, and game show personality, among other things, before earning the right to a show with his own name in the title. But the role of outlier, especially in his NBC days, gave him an unpredictable edge that differentiated him from his mentor and late-night lead-in, Johnny Carson. The Tonight Show was a traditional, controlled ship with an extremely skilled captain at the helm; as host, Carson was as reassuringly smooth as a sheet of wet glass. Late Night With David Letterman, on the other hand, was uncomfortable, unpredictable, weird, and occasionally even violent. Personality-wise, its host was no sheet of wet glass. He was more like a strip of scratchy Velcro. Yes, sometimes quite literally.

“I didn’t know if the stupid stuff would alienate people,” Letterman said in a recent interview with the New York Times regarding his early days on NBC. “I didn’t know if the traditional stuff would be more appealing. And then, when I look back on it now, of course the answer is, you want to do the weird thing.”

The weird things, in Letterman’s early days, involved asking often blunt questions of high-profile guests, a habit that eventually led to him being called an asshole by Cher; strapping a camera to a monkey and letting him run unattended through the studio; using a bullhorn to yell at Jane Pauley and Bryant Gumbel during a live taping of a primetime Today show special (“My name is Lawrence Grossman, president of NBC News. This primetime program was my idea, and I’m not wearing pants!”); or bursting without authorization through the doors of General Electric, NBC’s then-new owners, with a fruit basket. Rather than ingratiate himself with his corporate overlords, the network, or the show business bigwigs who served as his guests, Letterman became a wry rager against the machine with a Midwesterner’s self-deprecation, a combo that made him wildly popular with younger viewers. It may be hard for anyone under the age of 35 to grasp what I’m about to say since they’ve spent most of their lives thinking of Letterman as that grumpy old guy who still trots out Top 10 lists and, back in 2009, was embroiled in an unsavory sex scandal. But in the 1980s, watching David Letterman felt almost dangerous. If it’s possible for an entire generation to have a shared comic sensibility, then it seems fair to say that Generation X’s sarcastic, anti-authoritarian streak was best reflected and defined by Saturday Night Live in the 1970s, Late Night With David Letterman in the 1980s, and The Simpsons in the 1990s.

After Letterman moved over to CBS in 1993, he gradually began to sand down his more pointed corners. That didn’t stop him from sparring with Madonna, or bombarding Paris Hilton with questions about her stint in prison, or speaking about the Leno/Conan debacle without even attempting to disguise his schadenfraude. He wasn’t dangerous anymore, but he was still a man hob-knobbing with Hollywood types every night of the week, yet maintaining his distance from celebrity culture. Letterman has always appeared to have some genuine friends in show business, Bill Murray, Robin Williams, and Michael Keaton among them. But every time a famous guest mentions the idea of, say, having dinner with Dave outside the framework of his TV show, it’s obvious that Letterman is never going to make that reservation. For example, he’s made it very clear, on numerous occasions, that he adores Julia Roberts. But it’s also pretty clear that those two ain’t planning Fourth of July family vacations together at Clooney’s place on Lake Cuomo.

After more than thirty years on television, Letterman is still the outsider. Because of that, he has been and still is the only one of his kind in late night. Consider his colleagues on other networks. Jimmy Fallon – who previously starred on Saturday Night Live and in mainstream rom-coms, and is married to Drew Barrymore’s producing partner – counts a number of bold-facers as his buddies. Jimmy Kimmel does, too; when he got married two years ago, his wedding guests included Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, and Jennifer Aniston. James Corden, now in the post-Late Show slot, is, by virtue of his new-ness to American audiences, an outsider of sorts. But he’s also an “outsider” who recently co-starred in Into the Woods opposite Meryl Streep, Emily Blunt, and Anna Kendrick. Even the hosts whose work is most obviously inspired by the Letterman sensibility – Jon Stewart, Conan O’Brien, and Letterman’s soon-to-be successor, Stephen Colbert – seem like the kind of guys that would be perfectly comfortable at an awards show after-party, in a way that Letterman simply would not. As O’Brien himself wrote in a recent Entertainment Weekly tribute to his idol: “Dave’s show was that rare phenomenon: a big, fat show business hit that seemingly despised show business.”

By the way, there’s nothing wrong with hosting a talk show and not despising show business. Hosts are entertainers, after all. It’s natural for them to have friendships in the industry. But the fact that Letterman maintained an arm’s length from the prepped and primped guests who bound on to his set every night kept him honest, honest in a way that made his more serious moments – including his comments post-9/11 – that much more meaningful. True, his candor may have made Letterman seem brusque or curmudgeonly at times. And clearly, as that sex scandal proved, Letterman wasn’t always forthright about what was happening behind the scenes of his show. But he was always someone who could be trusted to ask the smart question and make a bold statement.

Imagine a current late night TV host turning to Arnold Schwarzenegger as he boasts about his next movie and saying, “Those steroids apparently don’t affect your ego, do they?”

Imagine a current late night TV host beginning an interview with Sean Penn by asking him about a bar fight he recently got into, then pressing for more details, while allowing Penn to smoke a cigarette as he shares those details.

Imagine a current late night TV host devoting the entire beginning of his show to blasting the company that now, effectively, cuts his checks, as Letterman did after G.E. merged with RCA back in 1985.

No one would do those things in 2015, including, most likely, present-day David Letterman. But for many, many years, Letterman was mainstream late night TV’s great misfit, its anti-Prom King. Scratch that: he was its King, period. And one of the key reasons he ruled is because he refused, at all times, to acknowledge he was wearing a crown.