How Real Is ‘Halt and Catch Fire’s Take on 1980s Computer Technology?

In the Wild West of the Texas Silicon Prairie circa 1985, competition at the bleeding edge of computer technology development was unrelenting. In last Sunday’s episode of AMC’s 1980s period drama Halt and Catch Fire, Gordon discovered that another company had taken his idea for custom built computers, and Cameron saw her company stolen out from under her as Mutiny became Westnet.

This cutthroat atmosphere of constant iteration and simultaneous development is exactly what series co-creators Chris Cantwell and Chris Rogers want to portray. They’ve placed their characters within the context of the real world and allowed them to represent a portion of the PC revolution that took place away from the tech superstars.

“We felt like there was a version of the story of the rise of PCs and the internet that had it all coming through Silicon Valley, through these two companies, Microsoft and Apple, and these two guys, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, when in truth it was this enormous industry spread across our country and all these little role-players,” Rogers says. “These people are so eager to share their contributions to something that turned out in hindsight to be phenomenally important, but at the time was probably not super sexy and easy to explain to your friends when you went home at night.”

As in AMC’s other hit period piece, Mad Men, Rogers points out the companies in Halt and Catch Fire are designed to plausibly exist alongside the real companies that actually drove innovation at the time. Cantwell explains that it made sense to insert new players into the Texas computer scene, since just about every company was trying its hand at computer building at the time.

“We wanted to exist within the cracks of history, and what was nice about this industry is that it really allowed us to do that,” Cantwell says. “This was a time when people were innovating right on top of each other, and it was really a case of who gets to be right first—as opposed to who has the right idea, period.”

As a result, the characters’ technology developments feel era-appropriate. Advancements like placing chips on both sides of the motherboard and using a broadband cable to link one computer to another could easily have been made by people like Gordon (Scoot McNairy), Donna (Kerry Bishe) and Cameron (Mackenzie Davis), working in smaller start-ups and garages.

“As we’ve gotten a little more in the foothills of the internet, occasionally it may have been necessary to compress some history, but we really like to have at least a plausible defense,” Rogers says. “At least some corner of technological consultants or the internet or history that backs us up.”

So far, the creators’ efforts to find historical validation have paid off, as Halt and Catch Fire has earned praise for its tech-savvy writing. Even Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak recently praised the show for its authenticity.

Cantwell and Rogers turn to books published at the time, experts from the field and even relatives to make sure that the technology created in the show remains properly in line with what was possible in the mid-80s, and to help polish the technical dialogue. In 1982, Cantwell’s father moved his family from Chicago to Texas to work as a computer salesman at a company similar to Season 1’s Cardiff Electric, so Cantwell’s first inspiration for the series came from his own upbringing.

For more technical information, the co-creators rely on the expertise of people like Carl Ledbetter, a computer engineer and professor of mathematics who has worked for companies including IBM, CompuServe and Control Data. Ledbetter has been one of the show’s primary tech consultants since the computer building scene in Gordon’s garage all the way back in the pilot.

In Season 2, as the focus of the show moved to networking and precursors to the internet, Cantwell and Rogers sought more advice from Bill Louden, who founded General Electric’s 1985 online service, GEnie. Louden also has experience designing games and other programs for CompuServe.

The future of the show’s online gaming service Mutiny looks bleak at the moment, as the resurgence of console gaming looms with the introduction of the Nintendo Entertainment System and Cameron struggles to deal with West Group’s hostile takeover. But she and her team could still have important developments ahead, given the trajectory of the real life inspiration for Mutiny, PlayNET, an online software developer which eventually partnered with the company that would become America Online.

“In tracing some of those stories back to how these big monolith companies of the ‘founding days of the internet’ came to be, you find these smaller companies that had one idea and then segued into something else and then segued into something else, and then partnered with this person and this other entity and ended up forming those places that we all remember in the beginning,” Cantwell says.

The creators didn’t limit their consultation to just major tech players like Ledbetter and Louden. The two cast a wide net, seeking out journalists like Paul Carroll, who covered the tech industry for the Wall Street Journal in the ’80s, and anyone else who could to give them a better understanding not just of the business but also life as a computer geek at the time.

“We really went to these guys for the technical expertise in terms of the dialogue, in terms of what we wanted the characters to do with the machines themselves, but also for the anecdotal, human stories of their experiences on the ground level,” Cantwell says. “What was a Thursday like at CompuServe or IBM or Control Data? What was it like to crack open a computer on the weekend and really get your hands dirty with a buddy?”

As the show has progressed, even the cast and crew have gotten carried away with the research. Associate producer Nathaniel Smith volunteered to design all of the Commodore 64 screens for Mutiny, a skill the co-creators didn’t even know he had when they brought him on for Season 2. The actors, particularly Davis as Cameron, always need to know what their characters are typing.

“We had grips sending our producers emails being like, ‘actually, I think it needs to be mainframe singular in the script here,’” Cantwell says. “Everyone was just so vigilant because they were having so much fun with the technology of the day that it kind of spread like a virus.”

From TV Guide Magazine

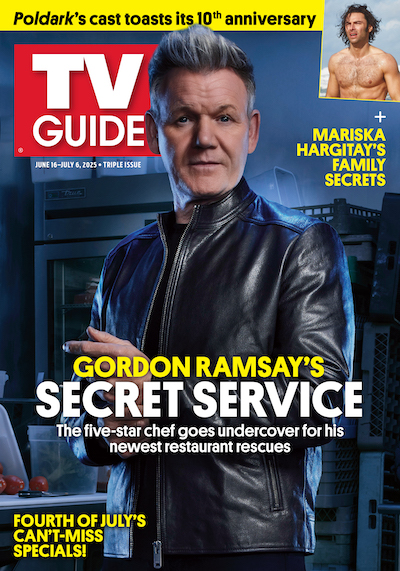

Behind the Scenes With Gordon Ramsay: 20 Years of Cooking Up TV Hits

The celebrity chef reflects on redefining culinary television and his fiery journey Hell’s Kitchen to Secret Service. Read the story now on TV Insider.