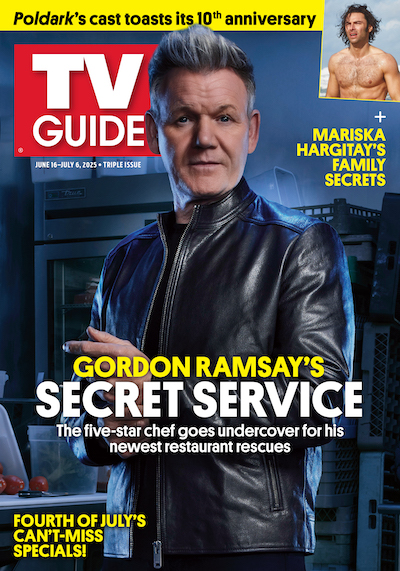

Mad Men’s True Story, From Start to Finish

Matthew Weiner established himself as a sitcom writer in the late 1990s, toiling away on such shows as The Naked Truth and Becker. But on the side, he was working on a different kind of project: a drama set in the 1960s New York advertising world.

“I paid someone to do research for me,” Weiner recalls. Back then, the Internet was still in its infancy stage, “and I didn’t know how to work Prodigy [the early 1990s dial-up service], so they went to the library.”

With all the data he had collected, Weiner finally started jotting down ideas in his office on the Paramount lot. “Then between the second and third season of Becker, I pulled the trigger and wrote it. I sent it out, and nothing really happened for a couple of years.”

Still, because he was considered a sitcom writer. “People were like, ‘who are you?'” Weiner’s manager eventually got that early Mad Men script into the hands of The Sopranos creator David Chase, who immediately offered Weiner a job writing for the HBO drama. Weiner, who at that time was working on Andy Richter Controls the Universe, moved to New York.

Weiner’s tenure on The Sopranos gave him enough credibility to dust off Mad Men and pitch it again. In 2006, AMC—a struggling cable network looking for its first major series—bit. Seven seasons later, Mad Men has been widely hailed as one of the greatest dramas in television history, star Jon Hamm has become a household name, and AMC is a cable force. As the show returns April 5 for the final seven episodes, its stars, executives, and producers recount in this extensive oral history how the world went mad for Men.

Weiner: Everything in life that is good news does not happen overnight. You do not get a phone call, you do not get plucked out of a stool in a drug store and suddenly get to make your own TV show. The script had a pretty good reputation at this point because it had vaulted me from half-hour comedies on to The Sopranos. But still, no one wanted to make the show. I would meet with people and they’d be like, “This is a great writing sample. I can see why [Chase] hired you. So what do you really want to do?”

Rob Sorcher (former executive vice president of programming and production, AMC): We really wanted our own Sopranos. We were an independent company, and didn’t have a signature series that people were talking about. There was a fear that AMC would be dropped from cable systems [if we didn’t get one]. But the notion of going out and getting your Sopranos on the first time out, I scoffed at that. I knew what HBO went through to get that show.

Ed Carroll (chief operating officer, AMC Networks): We were not overly concerned about having a ratings hit at the time. What we were really looking for was distinction.

Sorcher: I hired a head of scripted programming, Christina Wayne, and I didn’t even hire her full time because I wasn’t sure this was going to work out. Christina went to Matt Weiner’s agent and asked what he had lying around. We didn’t have the time or even the people [to develop something from scratch]. That script was in the desk drawer for five years, it had been passed on. Matt came in and gave this powerful pitch. The real question was, how were we going to do it? Our programming budget was so low. And it was a period piece, about advertising. Everything said: “Don’t green-light this show!” But I just needed to win awards. A lot of those handcuffs were removed.

Kevin Beggs (chairman and CEO, Lionsgate Television, which produces Mad Men): I heard Rob had taken a job at AMC doing originals, which I thought was funny because they run reruns of movies. But I got a call from him saying, “We’re going to jump into series. We’ve got an amazing script, it’s from Matt Weiner, who’s been on The Sopranos. This is not going to be your grandfather’s AMC. We’re looking for a studio partner.”

Weiner: The industry response to AMC was negative, from both my representation and other writers that I knew. “Why are you gonna go there? You don’t want to be their first project. They’re not going to promote it. They may not ever pull the trigger on it. No one’s going to see it. You’re squandering an opportunity.” But they wanted to make the show. They were super enthusiastic themselves. They treated me as a showrunner from the beginning.

Beggs: There were certainly questions from our international distribution guys about the viability of a period show that was so insular and so

focused on one aspect of American business life. Plus, basic cable was not yet the hotbed of auteur-driven programming it has become. We just couldn’t make the numbers work. So AMC made the pilot on their own.

Weiner: That pilot cost just over $3 million—and it looked like three times that. We couldn’t afford to film outside. I had this idea that a very detailed interior would be just as exciting to the audience as re-creating Madison Avenue.

Vincent Kartheiser (Pete Campbell): Matthew Weiner was set on one guy [for ad-man Don Draper]: Jon Hamm.

Weiner: Writing the role, I was thinking about James Garner. He’s handsome, charming, and also really cynical. But at the time there was an antihero atmosphere in TV, and people like Jon were being cast mostly as villains. [AMC] suggested a couple of British actors, but I didn’t want to do that. Don Draper’s big secret is not that he’s British.

Hamm (Don Draper): It was the best pilot I’d ever read. The only other time I’d had that experience was when I read the West Wing pilot. But they cast Rob Lowe.

Weiner: I had this litmus test: At the end of the pilot when you find out Don Draper is married, are viewers going to hate this man? When I met Jon, it was like, “No, they’re not going to hate this guy.” There was some question about his sex appeal, which is now legendary.

Hamm: You’re not playing Superman. You’re not playing the embodiment of truth, justice, and the American way. So it’s not necessarily fun to be in Don’s headspace. But it is challenging and attractive as an actor to get the opportunity to play that moral ambiguity.

Kartheiser: It was a battle to convince the studio and the network [to cast Hamm], but I was told, if they got that guy I would play Pete Campbell. He was the actor they thought I would match up well with.

John Slattery (Roger Sterling): I was called in to audition for Don. There’s a little disappointment when someone tells you they want you to read for Don Draper and you do all your homework [and] then they say, “We already have this guy, but we want you to play this other guy.” I met Jon shortly thereafter and I was like, “They do have that guy.”

Weiner: I didn’t approve of the trick, but whatever gets you there. I heard John wouldn’t come in otherwise. Then I had to talk him into being a part of the show.

Slattery: I was wary. Matt Weiner claims I was in a bad mood the whole time shooting the pilot. And I don’t think I was fully invested while shooting the pilot—there wasn’t very much of Roger in that first episode. Matt did say, “I promise you, this will be a great part.” He was right about that.

Elisabeth Moss (Peggy Olson): I remember walking out of [reading for Weiner]. I called my manager and said, “I have to work with that man.” I didn’t even know anything about advertising. I mean, I didn’t know anything about that world or anything about the 60’s.

Weiner: Elisabeth was the second person who auditioned for the show and the first person to audition for Peggy. I was like, “Who is this actress?” The casting people said, “There’s nobody like her.”

Moss: It’s the first pilot I’d ever done. The pilot script was so good, it was definitely one of those things that all the actors in New York were buzzing about.

Christina Hendricks (Joan Holloway/Harris): I originally got an audition call for Peggy. I told them, “This is a role for someone in their twenties.” Weeks later, I got the audition for [office manager] Joan. I was called back to read for the part of [illustrator] Midge, and then once more for Joan. It was that point in pilot season where as an actor you reach peak exhaustion and frustration. And at the time, there was no indication that any of the roles would turn into series regulars.

Weiner: Once Christina came in and read for Joan, she became a major character in my mind.

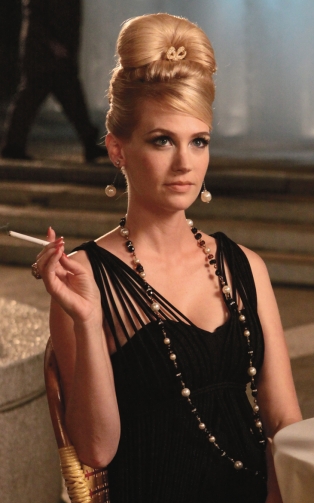

January Jones (Betty Draper/Francis): I went in to audition for Peggy, but Matt said, “There’s this other role…” He was struggling with the network about Don’s domestic life. I don’t think [the network] was as interested in finding out about who Don Draper was at home. Matt fought back on that.

Kiernan Shipka (Sally Draper): I was literally six years old. I didn’t have too much interest in what was going on in the show. At the beginning I was just given my scenes so I was just concerned with the Sally portion of the storyline and what was affecting her. Obviously I knew a general idea of the show and all that, but it wasn’t until later on that I started reading the full scripts and going to the table reads.

Kartheiser: My agent would come to me with scripts and I’d go, “That sounds great. But what’s going on with that show I auditioned for months ago?” There was just something about the [Mad Men] script. It wasn’t about crime or like anything else on TV at the time. I was like, “My God, I want to go to a place where I get to say those words.”

Sorcher: Matt asked Alan Taylor to direct while all his buddies on The Sopranos were on hiatus. They shot the pilot in 10 days in Queens.

Weiner: We were making a period show at the same time [the movies] Across the Universe and Revolutionary Road were filming in New York City. Just getting costumes for the extras was impossible. We were the least important ’60s project being shot in America.

Hamm: There was no star of the show. There was no person who was this big celebrity that we were circling. We were all hustling actors who wanted to do their best.

Weiner: Everyone took advantage of the fact that basic cable had different rules, and we were able to hire a bunch of actors who were not yet household names. Big names weren’t interested in being in a show on AMC.

Hendricks: My agents dropped me right after I did the -pilot. They were like, “We warned you not to do this AMC pilot because we’re not going to make any money.”

Moss: I feel like an old lady now when I say to people, “I remember when AMC was nothing.” When we started, we would say “AMC” and people would either think that we had said “A&E” or they would say, “don’t they just do movies?” Nobody understood the concept of this network doing a TV show. It was this huge risk and this uncharted territory.

Hendricks: I was scared because I thought, period pieces are expensive and difficult and people aren’t watching those kinds of shows. But my heart was just tugging me towards it.

It took nearly a year between the pilot and Mad Men’s launch, as Weiner took on the task of turning his vision into a regular series. Production moved to Los Angeles, and Weiner shared his vision for Don Draper and the entire series.

Weiner: There’s seven years between when I first wrote the pilot, and then writing the second episode. A lot about my vision changed in terms of how the storytelling would be done. Ultimately it was done very much in the pilot the way we continued to do it. But I didn’t know if it was just going to be a premise, or if we were going to be able to do something like that every week.

Beggs: [With the pilot] I had something to show, and we finally negotiated an agreement to produce the series. [Lionsgate vice chairman] Michael Burns’s father was an advertising executive who represented tobacco companies, so he had a personal connection to Don Draper. Our international guys upped their numbers. [Lionsgate COO] Sandra Stern negotiated a licensing arrangement that was acceptable to everyone.

Weiner: AMC said they were going to pick it up in June. But they didn’t have a studio partner until late September. And so I was finishing The Sopranos, but I had almost a year to think about what was going to happen in the show. I had a template of what the structure of the season, which was based on the movie script that I had written, The Horseshoe. It was Don Draper’s back story.

Sorcher: Our first-season budget was around $2 million an episode. There were moments where we weren’t sure we could deliver the show the pilot promised. Matt was very concerned. There were excellent financial reasons to get Lionsgate on board. They knew what they were doing.

Beggs: We had to set up a new financial template for the show. Amazingly, Mad Men, which is so dialogue rich, was shot on a seven-day schedule. That’s incredible. Most broadcast shows start at eight days and inflate from there.

Slattery: I needed a job, and Desperate Housewives called, and it was in between Mad Men having shot the pilot and starting series production. I called Matt and he wasn’t too happy about it. I told him, “I need to do it. I need to make money before we start.”

Jones: I didn’t find out until a few days before shooting how involved I would be. It was intimidating, the subject matter and the things I was dealing with, the psychological warfare of what Betty was dealing with and the physical results of that, the shaking, it was daunting to get it right. Not knowing who she was yet and how I was going to play with her and find her voice.

Robert Morse (Bert Cooper): They had already filmed the pilot and were back in Los Angeles [when I auditioned]. I walked in the door and there was a young man who was handling scripts. I was a little nervous and said, “Hi. I have this script here. I don’t quite understand what I’m reading. Can you understand this?” The young man said, “Oh, don’t worry about it. You go in, you’ll be fine.” I walked in and, my God, Matt Weiner was the boy. I was so embarrassed.

Weiner: He thought I was a production assistant! John Slattery had not committed to more than a season at that point, so I needed to create more of a world at the agency, just in case. Eccentricity is something you get when you hire Robert Morse. He said “goody” in the audition. And I put it in the script.

Morse: All of the things that were mentioned in Mad Men, I lived them. The advertising agencies on Madison Avenue that I used to travel to do voice-over work. Who would know that I would be thrust into Mad Men and go back to that period again. I remember arriving my first day and seeing all the secretaries at their desks, and it resembled the opening number in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying [which Morse starred on Broadway in 1961].

Finally, a premiere date was set for the show: July 19, 2007.

Beggs: It was the most awesome marketing and public relations campaign that I have ever been associated with, to launch a show with unknowns on an unknown network.

Weiner: We had an unusual amount of secrecy from the very start. January Jones, for instance, was not part of the initial press launch because I did not want the audience to know that Don was married. I had this confidentiality threat on the cover of the script, which I borrowed from The Sopranos almost word for word. Everyone around me thought it was amusing. They were like, “You’re lucky if anybody cares about this show.”

Moss: I am now a disciple of Matt Weiner and his idea of keeping secrets. I hate spoilers. Matt would faint if he knew anyone on our show was live tweeting during an episode, because you’re supposed to watch the episode, not look at Twitter.

Hendricks: I thought at first, “Oh boy, who’s watching this show, are you serious?” It was a bit over the top. But it was quite smart and it came from an educated place. I’d never been on a show that someone cared what happened the week after.

Charlie Collier (president, AMC): The lead-in to the Mad Men premiere was Goodfellas. We thought, take an iconic Scorsese film, filled with a lot of dark rooms and a bunch of men who think they are beyond the rules, and use it to launch our epic new series.

Sorcher: Not many people tuned in. There was a considerable amount of angst. That concern went away when the critics started writing about the show, even in the face of mediocre ratings at the start. It was the critics who ensured that this show got renewed.

Slattery: It took a while to make a dent in a popular way.

Carroll: You never green-light your first scripted series and expect to collect an Emmy for outstanding drama. It was a nice surprise. Then the show began to explode—you would see it in the style pages, references to Don Draper in the sports pages. It started popping up all over.

Season 1 ended with Sterling Cooper partner Bert finding out Don’s shocking secret (his real name is Dick Whitman, and he stole a dead soldier’s identity) and Don’s secretary, Peggy, giving birth to account man Pete Campbell’s baby.

Moss: I had no idea it was going to go where it went. I just thought Peggy was going to be a secretary for a while. But after she slept with Pete at the end of the pilot, it immediately sets up, “Maybe she’s more complex and interesting than that.”

Kartheiser: Nothing Pete does ever surprises me.

Season 2 was set a year later, in 1962.

Weiner: The skipping forward was a reaction to my fear that I did not have enough story. I felt that picking up the day after Peggy has the baby would just be too soapy.

Moss: The end of Season 2 when Peggy tells Pete about the baby and that she gave it away was one of the most beautifully written scenes I’ve ever been given.

Kartheiser: When it came to Peggy, I don’t know if it was ever about bedding her as much as it was something that gave Pete a sense of power that he lacked in his life. I think in some ways he hasn’t really graduated from that.

Season 2 featured many shockers, including Joan’s rape by fiancé Greg (Sam Page).

Hendricks: I was proud of how we did it. But I was surprised, and sometimes outraged, at the way that people phrased the conversation: “Remember that episode when Joan kind of got raped?” I think that’s unfortunate and a bit ignorant,

Weiner: You don’t want to be exploitive. I wanted to show that in my research, this was so common. The thing that was shocking to me was that there was a debate in the public about whether this was rape.

But Weiner says what generated even more controversy was the episode in which Don and Betty leave a pile of trash on the grass after a family picnic.

Weiner: I had to explain to the actors, because they are younger than me, that people used to just dump trash out and they would not look back. I had an overarching interest in the passage of time and showing certain things, like New York City becoming more dangerous and louder and more violent. Obviously the lawn-mower incident later in Season 3 [when a joyriding employee runs over the foot of an executive from the agency’s new British owner] is a dramatic moment that defined the show in many ways. We got the idea from stories we had heard about extremely dangerous, drunken behavior happening in these offices.

Slattery: Then there was the episode where I sang “My Old Kentucky Home” in blackface. I realize you can’t pick—you go where the character and the story go. But that was jarring. I remember the reaction of the first person who saw me step out of the van: It was an African-

American motorcycle cop, with his mouth hanging open.

At the end of Season 3, Weiner dissolved Sterling Cooper to form a new agency. And, after years of Don’s philandering, the Drapers’ marriage was over.

Weiner: I was inspired by Weeds, where creator Jenji Kohan just burned down the entire town. It was a tough thing to get rid of the Sterling Cooper offices. I was superstitious about losing that set, and it was a huge financial commitment from Lionsgate to allow us to start over.

Jones: Initially people felt sad for Betty. I got a lot of sympathy. But when she started to gain some courage and speak out, and not be OK with some of the things that were happening, it was very interesting to see the audience decide that they didn’t like Betty. A lot of men got upset when she cheated on Don at the end of Season 2. “How could she?” It was pretty hypocritical for people to be upset about that. People wanted Don and Betty to get back together. It was so unrealistic and dysfunctional, but fans loved their dynamic, as ugly and flawed as it was.

Morse: There were more women with their arms around [Don] than ever. I think we were the first Fifty Shades

of Grey.

Hamm: When people would say, “Oh that Don Draper, he’s such a terrible guy,” I’d say, “No, he’s misunderstood.” I’m always rooting for Don. People have their favorites on the show. I think some people are always rooting for Peggy and some people are always rooting for Joan, and maybe there’s a portion of the audience who’s rooting for Pete. A part of the attraction of the show or part of the sort of narrative that the show creates is that you’re invested in one of these characters, ideally Don.

Weiner: I was not going to spend the rest of the series playing cat and mouse with that marriage. But when we started Season 4 and Don was divorced, I started having second thoughts, because I realized there was not a big tradition in American culture of telling a story about a divorced man. I came to the conclusion those kinds of stories weren’t written because the men didn’t stay divorced very long.

Jessica Paré (Megan Calvet-Draper): After the first time Don and [his new secretary] Megan kissed, one of the guys in the costume department said, “It was nice knowing you.” Then our propmaster came into my dressing room the week before we were shooting the second-to-last episode of Season 4, and she said, “I need to measure your ring finger.” I was so overcome.

Weiner: [Don’s proposal to Megan] was the act of a man trying to start over. The impulsiveness of it, that is pure Don Draper: “Let’s get married right now.” Don had an idealized version of that relationship, which really didn’t include anything Megan wanted. As soon as she expressed a desire to follow her own dream [of acting], it became a rejection of Don. Megan is the first contemporary woman on the show, in terms of her ambitions and how she

asserts herself and what she thinks she’s entitled to.

Joan asserted herself by making the tough decision to sleep with a sleazy Jaguar executive in exchange for a partnership at the firm in Season 5.

Hendricks: That was based around many real stories that Matt had heard from women [in that era]. There were a lot of cheerleaders for Joan. I’d run into women in bathrooms and they would be like, “Girl, I would’ve done that.” And other people were upset.

Paré: It’s definitely shocking to see some of the treatment of women on the show, but for me, it’s turning a mirror on our time and how women still aren’t paid as much as men are.

Weiner: It’s been accepted as a realistic situation. The only thing not realistic about it is I don’t know if anyone got a partnership out of it. But besides someone peeing in their pants in the office, the story of a woman having to sleep with a client to advance was relayed to me on many occasions. I knew Don was going to give this great pitch for Jaguar, but you would have never listened to that pitch if you knew that Joan had slept with the guy already. So [writer] Semi Chellas came up with this flashback structure, and it allowed both things to happen. I don’t think people understand: Matt Weiner does not do this by himself. I speak about myself in the third person because I don’t think people realize, I’m not that person. You cannot do 92 hours of television without a real brain trust of people.

In 2010, Weiner’s contract expired and the tense negotiations played out in the press. Eventually, Weiner signed a new three-year pact worth a reported $30 million, and the show was picked up for Seasons 5 and 6, with an option (later exercised) for a 7th.

Weiner: That was really bad, and hard. There had been a renegotiation after the second season. This was not a renegotiation. This is someone who had a contract whose contract had expired. My contract was allowed to expire, and there were conversations going on between AMC and Lionsgate that I didn’t know about, of them working out business stuff. I didn’t hear about what was going to happen for a very long time. There were some demands being made about the running time, product placement, and the cast. I did not want to do it. There were all kinds of cost-cutting measures and control issues and I was like, “I thought we were in this together.”

Hamm: My thought was always that you’re not going to kill the golden goose. Everybody complains and then they eventually come to a deal.

Weiner: None of it was about money. I hope that became clear to people at that point. Including the [17-month] delay. I don’t know if that was clarified. That had been in the works for a while. AMC wanted to rejigger the schedule so Breaking Bad would go on during the summer. And we would move to the later time. Then somehow it became, I was holding out for money and they were going to have to delay the show. It wasn’t true, Charlie said it wasn’t true.

Collier: With each negotiation the entire goal was truly just to get us back to air with Matt at the helm.

Weiner: I knew in the end I had my pencil, and I could go work somewhere else if I had to. The cast supported me but no one was going to be able to leave if I left. For me, it was just another business story that I unfortunately didn’t understand what hardball meant. The great thing was being able to go back to work and pretend like it didn’t happen. There was so much more openness after that.

Over the years, viewers said goodbye to many characters, including Sal (Bryan Batt), a closeted gay man who was fired when he brushed off the advances of a client, and Lane (Jared Harris), a partner who hanged himself in the office after admitting to embezzling.

Weiner: There aren’t a lot of deaths on Mad Men. But if you get fired, you might as well be dead. There had to be stakes. Even when we had Peggy go to another agency, we did everything we could to convince the audience that Peggy was going to be a minor player at that point.

Moss: When she left Don to go work at another office, I had so many women tell me that they’ve either done that or it gave them the courage to do it, or to ask for something that they needed, or to stand up for themselves at their job. When I say goodbye to Don and I’m leaving the agency to go to CGC, that would probably always be one of my favorite scenes. I just thought that the way that she says goodbye was the way that someone would say goodbye. There aren’t a lot of tears, there’s not a lot of anger, and the way that he responds is so brilliant. He responds with this bitterness and also love.

Viewers also began flooding the Internet with conspiracy theories about Bob Benson (Josh Wolk) or wondering if hints had been planted that Megan might ultimately be killed by Charles Manson.

Weiner: It suggests a level of Byzantine plotting and symbolism that I don’t think we’re really doing. I hate to disappoint people, but I wish sometimes we were that subtle. Bob Benson was its own little accident. Casting had a lot to do with that. James Wolk, he really stands out.

The first half of Season 7 concluded with the moon landing and Bert’s death. Roger maneuvers a sale of the company, allowing for Don, who was put on leave after melting down during a Hershey’s pitch in Season 6, to resume his old position. Later, Don daydreams of Bert singing “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” giving Broadway vet Morse a chance to exit with a song and dance.

Morse: It was a lovely moment, I thought.

Weiner: In the end, they all got rich, but Bert is dead. And questions remain: Can Don and Peggy have a relationship again? Can Don and Roger have a relationship again? Can Don prove himself to new partner Cutler [Harry Hamlin]?

Hamm: When we first met Don, he was the master of his universe, although it was wobbly. We see him struggling with selling cigarettes. It’s a very quick realization that something is rotten. He’s living a double life, and that’s tricky. So, he’s set up to fail. It’s no accident that the credit sequence shows a man seemingly in charge of his environment and then the environment falls apart around him—and he falls. That has been the arc of the character for seven seasons—a fall. And so the hope is that he recovers or that the fall leads to something else, because nobody wants to see the splat.

Moss: For me, Peggy and Don will always be my favorite relationship on the show. I used to hear for so long, “Are they going to get together romantically or is it a father–daughter thing? Is it mentor–protégée? Are they enemies? Are they friends?” It’s all of those things.

Hendricks: [Joan and Peggy] is another relationship that flipped back and forth. Matt said early on that these women are never going to be friends. But there’s a mutual respect there and they’ve been learning from each other for so long.

Production on the final episodes of Mad Men wrapped last summer.

Hamm: I had to work every day, so I couldn’t really afford to just be emotional and sit around moping or anything. The last few days were fairly Don-heavy.

Slattery: I was surprised by some [of the finale]. Everyone has their story, and I was surprised by some of them.

Moss: If this is how Peggy’s story ends, I think it’s perfect and I think there is something to leaving it in a perfect place.

Jones: The audience will be surprised and nothing will be tied up.

Morse: Jon Hamm is the head. I have hardly ever seen, in the seven years, him go crazy or be upset of any magnitude. I think we all followed his lead. The atmosphere was one of great precision.

Paré: Jon is at the helm and because he gives a shit, he makes everybody be better at their work and he inspires people to give their best stuff.

Weiner: Eighty-five percent of our crew was there from the first season—despite all those hiatuses and unintended delays. This is a family. We’ve grown up together, and it was a place people came back to. It will always be home.

Hamm: We’ve gone through marriages and divorces and babies and boyfriends and girlfriends and ins and outs and so many ups and downs. I think it’s a wonderful credit to everyone on the show that we all still like each other.

Morse: My heart aches. I revel in the glory of all those performances. These were seven glorious years. I cherish them.

Shipka: Mad Men, in a way, has been my acting school.

Slattery: It was a parade of last days on the set. We would get an email that it was someone’s last day. Somebody would make a speech, we’d get emotional. And then finally there was the actual last day. We had a big wrap party and hung around until late. It was emotional.

Jones: Knowing I would never speak for Betty again, I was in tears the whole day. My last fitting, last table read, speaking for her for the last time, it was like someone died. I wasn’t expecting to react like that.

Paré: I have an idea for a spinoff. It’s kind of like the plot of Three’s Company, only it’s Pete and Ted and Megan.

Beggs: We have pitched Matt a million different spinoff ideas, but we’re like the unsuccessful ad agency that never gets that account. He knows he’s got a masterpiece on his hands and probably isn’t interested in a derivative of it.

Weiner: I’m not interested. And I won’t budge on that. I love that this is it. If people are left wanting more, then you did your job right.

In the bit, Aria (Lucy Hale) is seen snooping around her brother Mike’s bedroom when hot Andrew Campbell (Brandon W. Jones) and his giant biceps suddenly pop in, claiming that the Montgomery home’s door was open.

Or was it?

There are a lot of folks who suspect the friendly hunk—who shares the same last name as the farm close to A’s lair— might actually be “Charles,” the masked man keeping our girls hostage. Adding to the evidence: he listened in on Mama Hastings’ phone calls, he’s way too nice to be trusted, and there is no way this guy is a high schooler! So it is very possible he is secretly older and was at the same years-ago prom that “Charles” recreated in his giant dollhouse hideout, which would make him about the same as Melissa Hastings (Torrey DeVitto) and Jason DiLaurentis (Drew Acker). Is Andrew the long-lost tot we saw in that DiLaurentis home video?!

Pretty Little Liars, Season premiere Tuesday, June 2, 8/7c, ABC Family

From TV Guide Magazine

Behind the Scenes With Gordon Ramsay: 20 Years of Cooking Up TV Hits

The celebrity chef reflects on redefining culinary television and his fiery journey Hell’s Kitchen to Secret Service. Read the story now on TV Insider.