Nat Geo’s SharkFest Captures a First: Teen Tigers Working in Tandem

Preview

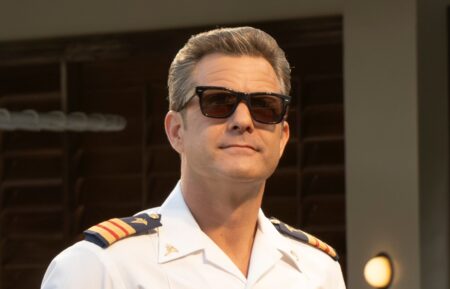

“Sharks have these superpowers. That’s why I got addicted as a kid seeing them on TV,” renowned underwater cinematographer Andy Casagrande (above) says. “When you give sharks personality, you give them a story, people care. And you protect things you care about.”

Casagrande kicks off National Geographic’s annual Sharkfest on July 19 with a doozy of a tale in World’s Biggest Tiger Shark? (8/7c). The cinematographer travels with marine biologist Kori Garza to the protected waters of French Polynesia in search of Kamakai, a female tiger shark estimated to be 16 feet long. While deploying a tethered drone to continue the quest after dark looks decidedly cool—”It’s like playing a live video game with sharks,” Casagrande says in the special—it’s two daylight dives that prove to be the most heart-pounding and informative (even if Kamakai remains elusive).

A local fisherman takes them to a remote lagoon, where he’s noticed a large number of tiger sharks, a typically solitary species. As the first researchers to study them, Casagrande and Garza realize they’re all juveniles and subadults—which means, topping out at nine feet, they’re smaller than fully mature sharks, but also more curious, bold and unpredictable. To find out why they’re congregating here, Garza, a master free diver who can hold her breath for up to four minutes, places Casagrande’s non-invasive Fin Cams on two sharks’ dorsals by hand. One of the sharks makes an immediate beeline for her safety diver, Pierrick Seybald, and we get the perfect, chilling view.

“Any time we get a Fin Cam on a shark, it’s like Christmas morning and you’re opening up a present; you don’t really know what you’re going to get,” Casagrande says. “In this instance, it was like a real live Sharknado. You’re like, ‘All right, let’s put it on this one because it’s right here and it won’t go away.’ When we got the Fin Cam on it, it just kept on doing what it was doing and, yeah, [gave us] that perspective of, ‘Oh no, oh no, oh no.’ The safety diver had plenty of experience and deflected it.”

That’s an added bonus for anyone watching this special: “You can learn how to interact with sharks,” he says. “A lot of people are like, ‘What do I do? Do I punch it in the nose?’ No, you don’t punch a shark in the nose for a number of reasons. First of all, there’s refraction. Everything looks closer underwater, and when you swing at a shark that’s actually not there, the next thing that’s going to make contact is its mouth. So it’s better to deflect them like a matador, or you can just slightly give them the Heisman, so to speak.”

Garza is so cool in the face of the relentless youth that she even takes the opportunity to adjust the fin cam. But just wait until you see what’s next. To test the team’s theory that these juveniles are working together, “learning to shark” in the safety of water too shallow for the hammerheads that would prey upon them, Garza jumps in with Casagrande’s 360 camera (above) hoping to film their coordinated efforts to investigate her. Soon enough, they circle her in unison, from every angle. After several tense moments of countless deflections, the sharks all disappear—only to return en masse, like an army. It’s believed to be the first time this kind of cooperation, which suggests the young sharks may hunt in a pack, has been filmed with tiger sharks, but Casagrande has captured the behavior before with a pair of great whites in Australia.

“They’re clearly communicating with each other,” he says. “These juveniles were kind of like a pack of high schoolers. ‘Hey man, let’s go out and party. What is this 360 thing? You go to the back, and I’ll go left and come around.’ It doesn’t seem to be a predatory approach. It’s more like they all just want to get in on the action. And then when some of them lose their confidence, it’s like, ‘Oh, Billy’s gone. Where’s Jim? Where’s Sara? Okay, I’m out of here, too.’ And then they regroup and come back.”

C0uld some of those sharks be Kamakai’s offspring, tolerating each other until they get too big to share a meal? Casagrande thinks it’s possible: “If you’re born with other shark babies in the same reef, why would you not hang out with another creature that looks identical to you, is the same size and eats the same thing? If you didn’t get your tail bitten off by the thing that just swam past you, you’re like, ‘Oh, he was cool. Let’s see what he’s up to.’ And then you not only have safety in numbers but the ability to cooperate, which is just beneficial. I don’t think we give sharks enough credit. We’re starting to, which is great.”

He hopes to return to Tahiti—perhaps to find the world’s smallest tiger shark, he jokes, and study the behavior more. But first, he’s also a contributor on Sharkfest’s July 23 premiere, Most Wanted Sharks (10/9c). This special is like TMZ for the sea, profiling some of the ocean’s biggest celebrities like big mama Deep Blue, considered to be the largest great white (20 feet) ever filmed; Colossus, the massive male known for his stunning breaches in South Africa (as seen in the Air Jaws franchise); and the adaptable bulls who’ve taken over a freshwater lake on a golf course Down Under.

The Most Wanted list begins with a few of the charismatic great whites who wow cage divers off Mexico’s Guadalupe Island. Casagrande’s favorite is Lucy (above), who’s thrived in spite of a damaged tail fin, which forces her to swim with a bit more swagger and makes her instantly recognizable. “It’s hard not to fall in love with great whites when you can see that they’re each individual, unique sharks,” says Casagrande, who first encountered her more than a decade ago, and even serenaded her with his “Great White Shark Song” (below).

At Tiger Beach in the Bahamas, other species share the spotlight. Fifteen foot tiger Emma—dubbed the most photographed shark in the world—is content to hang around dive groups for the snacks. (Tigers notoriously eat anything: tires, explosives, even a suit of armor.) Great hammerheads are typically solitary, but 17-foot Patches (below) mingles at the chum box.

Casagrande has placed cameras on her large dorsal fin, allowing scientists to study how she glides through the water, often tilted at an angle of 50 to 75 degrees.“It helps them travel vast distances, and it just looks cool,” he says of the energy conserving strategy. “Sharks always have some reason for the behaviors they exhibit and not just, ‘Oh, we’re going to eat people.’ If they were really out to get us, we would be in serious trouble.”

Sharkfest begins Sunday, July 19, on National Geographic, followed by two weeks of content on Nat Geo Wild, beginning Sunday, August 9

From TV Guide Magazine

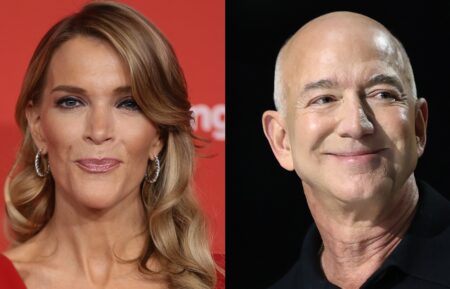

How 'Countdown' Recruited Jensen Ackles to Go Full 'Die Hard'

Countdown boss Derek Haas talks creating the character around Ackles, and the cast teases the “Avengers”-like team of the crime thriller. Read the story now on TV Insider.