Why the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Is Still the Biggest Event in TV History

Here’s a little-recalled fact about that distant day, 50 years ago, when human beings triumphantly first landed on the moon. Astronaut Neil Armstrong, piloting Apollo 11’s spiderlike lunar module (LM) built for the descent, touched down on the moon’s surface on July 20, 1969, at 3:17 pm Houston time. Meanwhile, CBS television had already been there for about 20 seconds.

“Yes, CBS ‘landed’ on the moon before the astronauts did,” explains the network’s then-correspondent and coanchor David Schoumacher, recalling the premature broadcast of landing animations. “CBS could time it exactly to the flight plan but since [the LM flight was delayed], CBS landed … and the astronauts were still saying, ‘Three seconds, two seconds.…'”

Even with a glitch, the live coverage of Apollo 11’s journey remains the most spectacular show in television history. The unparalleled eight-day space spectacle, culminating with Armstrong’s first step on the lunar surface, required “one of the earliest uses of a satellite to broadcast live pictures of a news event,” says Ron Nessen, then an NBC TV correspondent (and later, famously, President Gerald Ford’s press secretary).

The moon landing was seen by some 650 million people worldwide — matching the total viewership of the last six Super Bowls combined — in coverage that aired live everywhere except China and the Soviet Union. But the U.S.’s TV effort would not have happened if the networks hadn’t ostensibly taken the same 1961 pledge that President John F. Kennedy pressed upon Congress to “land a man on the moon before the decade is out.”

(Dennis Caruso/NY Daily News via Getty Images)

“The special effects unit at CBS News was a large group, 50 or 60 people, and they did nothing but plan years ahead for the Apollo mission,” Schoumacher says. As the effort began, in the early satellite days when most TV news outlets used film that had to be processed, “we didn’t have the ability to originate a picture down the street, much less a city away, much less a world away,” he adds. “But no one ever said, ‘We can’t do that.’ It was, ‘How do we do it?'”

The “how” included spending millions of dollars on “what if” contingency solutions to any broadcasting issues, often in concert with NASA. Networks ABC, NBC, and clear leader CBS — which had legendary Walter Cronkite as its news anchor — created and refined simulations of the Apollo rocket and the lunar module in action to make for interesting, informative airtime. NBC built a life-size LM replica to demonstrate the challenges Armstrong and copilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin would face.

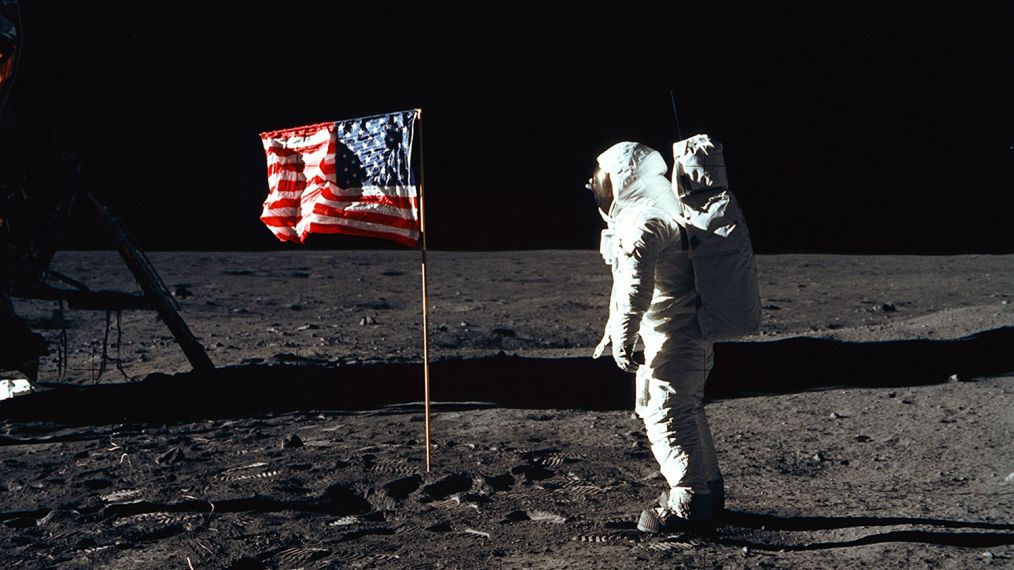

A black-and-white Westinghouse Electric lunar TV camera — one of 17 the company made in its $7.7 million contract with NASA — was mounted to the actual LM, and Armstrong positioned it so the world could see his descent and “one small step.” After some image adjustment on Earth 239,000 miles away, the camera was ready for its scratchy broadcast. (Just in case, astronauts also brought a 14-pound antenna, covered by 38 miles of gold-plated wire, to use if the TV signal proved unviable.) Finally, a network of 20 stations, interconnected with satellites some 22,000 miles overhead, carried the footage across the U.S. to Latin America, Europe, North Africa, Asia, and Australia.

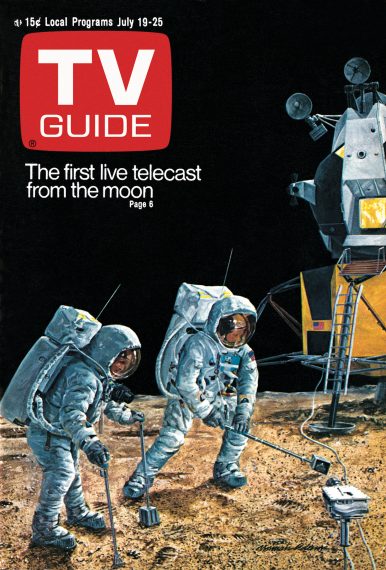

At CBS, Cronkite and special coanchor Wally Schirra — one of the seven pre-Apollo Mercury astronauts — logged 17 straight hours of coverage, dabbing their eyes when the LM landed safely. As Cronkite wrote in the July 19, 1969, issue of TV Guide Magazine, “It seems to me that this joining of technologies, of television and Apollo, demonstrates what is within our capacity as [humans] to do.”

(CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images)

For the millions who witnessed the momentous event, this was sci-fi come true. “It was a unity of purpose at the network as well as the nation,” says Schoumacher. “People now take it for granted, but any kid [with] an iPhone has a computer with more power than the NASA computers had back then. These were people doing something incredible.” —Robert Edelstein

Of course TV Guide Magazine covered Apollo 11’s mission and moon landing — “the most truly special television program in the medium’s history,” according to writer Neil Hickey. Written before the launch, but anticipating how the two-and-a-half-hour broadcast from the moon would unfold, the feature detailed what was set to occur: astronaut Neil Armstrong opening the door of the lunar landing module (LM), then activating the TV cameras transmitting back to Earth, and finally taking his famous first steps on the moon.

Once fellow astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin joined him on the moon’s surface, they would use additional cameras to transmit more space images as well as take still photos; they’d also collect geological samples before re-boarding the LM and, hours later, start their journey home.

CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite also penned a story for the issue, looking back over the decade-long space race from a scientific, political, and mostly broadcast perspective. Cronkite anticipated that Apollo 11’s time on the moon “will be the most expensive and extensive television coverage in history,” he wrote. “And I believe it will be the most exciting and historic event that I will have reported in 37 years as a journalist.”

We’re sure the show lived up to his expectations. —Amy Miller