The 5 TV Shows of the ‘80s That Rewrote the Rules of Fashion

For many Americans in the 1980s, the runways of New York Fashion Week might as well have been on Mars. Instead, would-be fashionistas from coast to coast took their notes from the TV characters that popped up in their living room each week. From Dynasty’s bougey glamour to Miami Vice’s casual coolness, game-changing style on TV inspired the masses and helped move fashion toward the more accessible industry it is today. Here, the brains behind five of those series’ designs reflect on their work and legacy.

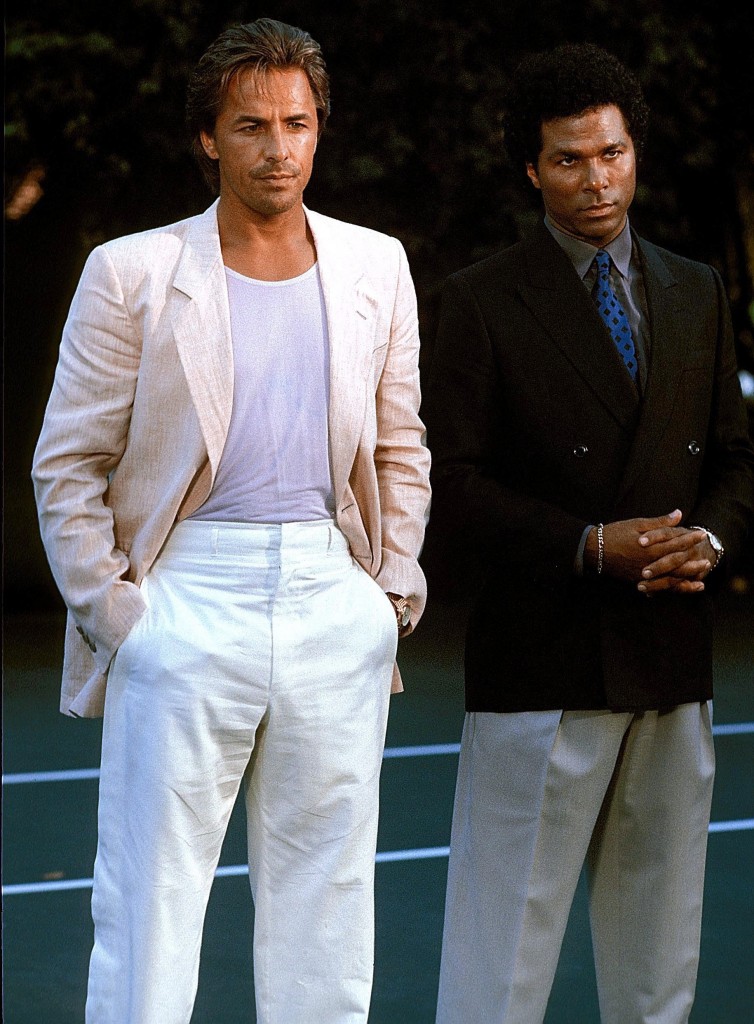

Miami Vice

Don Johnson, Philip Michael Thomas

Pants without belts, t-shirts with blazers, loafers without socks—Don Johnson’s detective Sonny Crockett ignited many a menswear trend. Good thing Johnson didn’t get his way. “He thought it should be jeans and a v-neck sweater and cowboy boots,” says Jodie Tillen, the first season’s costume designer. “Once we talked it out, he understood. Crockett was a guy who had no fashion sense at all, actually. He only wore it as a uniform.” That meant everything was about utility—why would Crockett waste a second on a belt?—right down to the swanky Ebel watches he wore in season one. Says Tillen, “He had to know what time it was!”

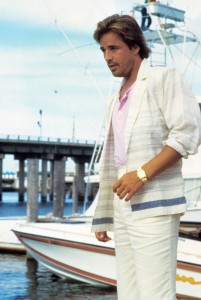

Don Johnson

Tillen credits Michael Mann, the show’s visionary executive producer, with creating the overall aesthetic—the t-shirt under a blazer was his idea, as was a dedication to pastels. And then there were those suits. While the collective conscious today remembers them all as Armani creations, that’s not the case. “There was not one piece of Armani clothing in the year that I was there,” says Tillen. “It’s too conservative—gorgeous, but very conservative.” Instead, she preferred the “crazier” styles of Versace.

Tillen left after Vice’s first season, passing the reins to Bambi Breakstone for the show’s sophomore outing. Breakstone did introduce some Armani, but her focus was on the then rising Hugo Boss. “We really didn’t have the budget I wanted, so I arranged to give them credit at the end of the show, and they supplied a lot of clothes in exchange,” she says. Breakstone evolved Johnson’s look, introducing what would become another of the show’s staple: rolled-up sleeves.

Realizing how small in stature many of the Latino men playing gangsters and drug dealers on Miami Vice were, she applied a lesson she’d learned as a student of costume history. She recalled how Queen Elizabeth I had worn incredibly wide garments, extending up to 25 inches off either hip. “By taking up that much space, it gave her authority over the room because people had to move out of her way,” explains Breakstone. So she dressed the men in bigger clothes. With minimal time for alterations, rolling up the sleeves was simply a necessity.

Punky Brewster

Soleil Moon Frye

Long before the concept of “personal style” launched a million Pinterest boards, precocious kid hero Punky Brewster (played by Soleil Moon Frye) was banging her own drum. With mismatched sneakers, funky color explosions and pop sensibility, she gave little girls permission to experiment. “Where a grown up would say, ‘Why?’ A kid would say, ‘Why not?’” explains Gene Doucette, the show’s original costume designer. “Kids don’t live their lives by that little 12-crayon box of Crayolas. They live by the 100-color box.”

So Doucette ignored what kids were actually wearing those days and focused on what they would wear if they had sartorial autonomy. Among his finds were two things he hoped would make the look special for the young Soleil: sun-shaped barrettes (her first name is French for sun) for her pigtails and moon-shaped earrings.

Doucette realized the show was striking a nerve when, during the first Halloween after the show’s premiere in 1984, dressing up as Punky was every kid’s plan. But what he couldn’t have expected was that 30 years later, magazines and designers would still be referencing the look—and not as a costume idea, either. “There was a freedom to it,” he says. “It was self-expression, which was unlimited.”

PHOTOS: The Craziest Outfits Worn by Cookie and Other Empire Ladies

The Dukes of Hazzard

Catherine Bach

While Catherine Bach’s sizzling character Daisy Duke would become synonymous with her thigh-revealing denim shorts, the original plan was to dress the waitress in a poodle skirt that matched the tablecloths at the Boar’s Nest, where Daisy waited tables. Bach was horrified. “Poodle skirts do not look good on anybody,” she says. “They can be cute and signify a timeline in America, but they’re not figure-flattering, and I just thought that was dreadful.”

Catherine Bach

So Bach headed home and brought in an alternative: a pair of jean shorts she’d cut from her own bell-bottoms. Extra-short from cutting higher and higher as Bach tried to get the sides even, the shorts were a hit with the producers. Bach, who had spent two years in design school, became in charge of making more. She estimates she created around 20 pairs, often out of size 4 or 6 Levi’s, for the show’s early episodes before a costume designer was brought on. (You can also thank Bach for that famous red bikini).

But producers, fearful of CBS sensors, required her to wear skin-tone tights underneath the shorts. “They got the thinnest, silkiest, finest pair of nylons and put those on me,” says Bach. So did she always wear them? “When I remembered,” she recalls with a giggle.

This spring, it will all come full circle for Bach, who says she’s opening up a store in Nashville in April to sell tourist items and other things she’s made. The name? Daisy Country by Catherine Bach.

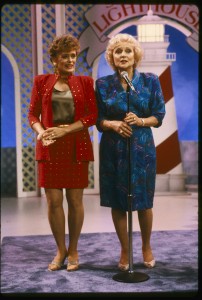

The Golden Girls

Estelle Getty, Bea Arthur, Betty White and Rue McClanahan

No show redefined “dressing your age” quite like The Golden Girls. Blanche, Dorothy and Rose wore bright, vibrant colors in modern silhouettes, pushing the bounds of how senior citizens were expected to present themselves. “The producers wanted to keep the women looking ‘up’ and youthful,” says the series’ costume designer Judy Evans (now Judy Evans Steele). “They didn’t want anything dowdy. They wanted the women looking good.”

Rue McClanahan, Betty White

Each of the leads had their own sense of style, based on the preferences of both the character and the actress. Rue McClanahan’s Blanche was unafraid to show a little leg or cleavage or both. Betty White’s Rose was more conservative, frequently wearing shirtwaist dresses. For Bea Arthur, Evans went with a “tailored, sophisticated” look because Dorothy “kind of lorded over the others.” She wore lots of suede boots and long skirts, but rarely heels because Arthur didn’t like them.

Viewers of a certain age couldn’t get enough. “The difference between a costume designer and a fashion designer is [the former is] designing for the person literally. With fashion, you’re designing for the ideal woman,” says Evans. “We didn’t have four ideal women, by any means. [That] appealed to a lot of people.” Evans was flooded with inquiries about her designs, and often, she’d pay that support back, sending fans a copy of a sketch and a fabric swatch to take to a dressmaker.

Dynasty

Joan Collins

When you think Dynasty, you think shoulder pads. But the late costumer designer Nolan Miller’s use of them wasn’t exactly revolutionary—designers like Norma Kamali were already all in. “[Dress] shoulders were three times the size of ours,” says Mark Zunino, Miller’s costume assistant who would go on to take over his company. “But that show got international recognition and so everybody focused on it.”

Linda Evans

The pads also had a very practical purpose for Linda Evans. “She had large shoulders, as did Joan Crawford,” says Zunino. “Nolan knew through [working with] Joan Crawford that rather than try to diminish them and make them look smaller, [you] accentuate them.”

Zunino recalls that when he first joined the show, he was shocked at the sheer decadence. “One of the first things that I sketched was a dressing gown for Joan Collins. It was a thick cashmere jersey with big sable cuffs,” he says. “That thing cost tens of thousands of dollars, and it was just on the screen for, like, 10 seconds.” But that attention to detail was crucial for Miller. “We’d hunt and hunt for these very extravagant, luxurious fabrics,” says Zunino. “And Nolan said, ‘It matters because it’s the way it makes the character feel when they’re wearing these clothes that makes them act the way they do.’”