‘We Dug Coal Together’: A Tribute to Justified’s Boyd Crowder

Walton Goggins is the kind of guy who loses a thought during an interview, doesn’t remember it by the time he has to jump off the phone, and calls back out of the blue the next day. “I just had to tell you I remembered what I needed to say,” he says, and launches into a five-minute monologue about the history of Harlan County and how it informs the needs and wants of his Justified character, Boyd Crowder. He speaks with the same energy, the same inherent charisma, that made Boyd one of the most compelling TV characters of the last decade.

In the final showdown between Boyd and friend/nemesis Raylan Givens (Timothy Olyphant) on last night’s series finale, it felt inevitable that Boyd would die—the only question, it seemed, was whether he would take Raylan down with him. But Yost and the writers turned that struggle into a metaphorical, rather than physical, one. Boyd refused to pull on the lawman, forcing Raylan to decide, once and for all, what kind of man he really was. Raylan chose to listen to his better angels, and Boyd ended up in prison, rather than a cheap pine box. “Putting that decision in Raylan’s hands was Boyd saying, ‘I know who I am, but who are you?'” says Goggins.

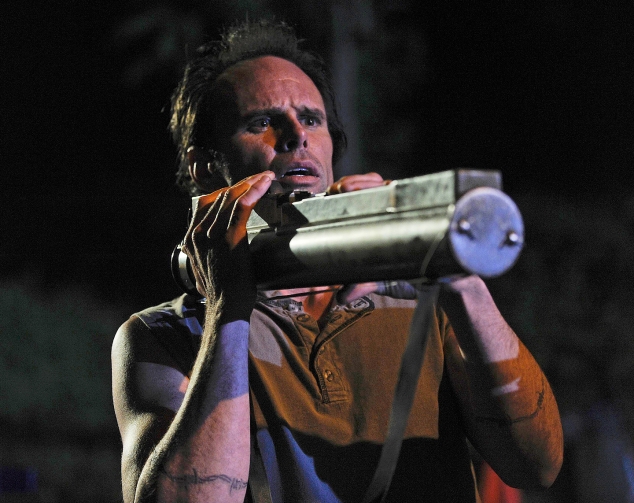

“Who Boyd is” largely depended on the last catastrophe to have occurred in his life. He began the series as a showman, loose-limbed and -tongued, drinking ‘shine and wearing camo pants and spouting Neo-Nazi nonsense he didn’t really believe, but which facilitated his desire to “get money and blow shit up,” as Raylan put it in the show’s pilot before shooting him and triggering a religious rebirth.

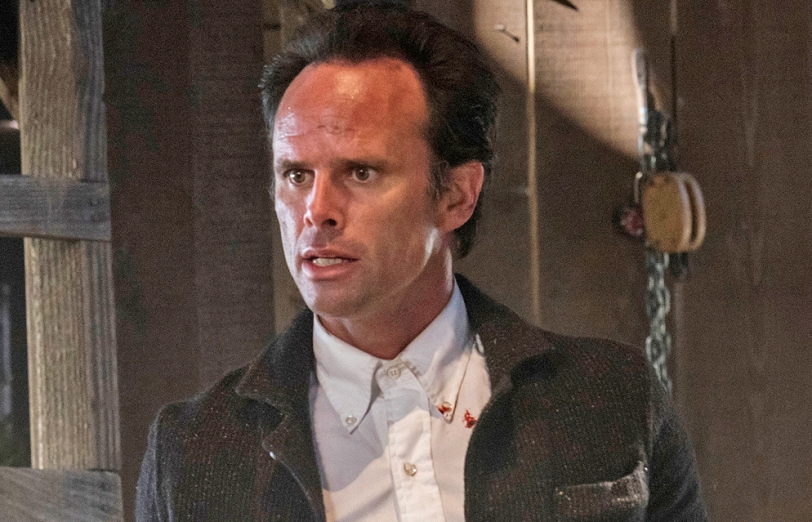

Over the course of the show, Boyd’s look morphed into something more respectable than “regular racist hillbilly”—collared shirts buttoned to the throat and vests with watch chains, black pants and pea coats; and he long ago ditched the skinhead credo (though not the tattoos). Only the verbosity remained: “You use forty words when four will do,” one of his enemies told him, half-admiringly, in Season 4.

Each wardrobe update came with a change in personality. (“We’re on what, Boyd Crowder 6.0?” Goggins cracked at the beginning of the final season.) As early as Season 3, Boyd had a come-to-Jesus moment with a loyal lieutenant having trouble with his boss’ multiple metamorphoses. “I just want to know which Boyd Crowder I’m being asked to follow,” he said. Boyd’s reply was a summary as accurate as it was eloquent:

“What if I told you I was the man who recruited you in that church, but then I also told you I was the man got shot; who found God; who betrayed his father? That I was a man who killed men, and gotten a whole bunch of men killed? See, Devil, I can’t discard my past any more than I can these tattoos.”

In the hands of lesser writers and a less capable actor, Boyd’s numerous transformations would read as creative flailing. But the common thread throughout those transformations was Boyd’s magnetism, which came out in full force whenever the opportunity to play orator came around.

Watching Boyd preach, whether it was the Word, on behalf of a mining company, or trying to win Harlanites to his side, was Justified at its best. Preacher Boyd came out once more last night, mere moments before we said goodbye to the character forever, as he evangelized to a group of fellow prisoners. “That was one scene I pushed for,” Goggins says. “I wanted that one last reminder to the audience of why they loved this guy.”

That love came in part from a recognition that in none of his iterations did Boyd see the criminal life as anything other than a means to an end: “He has a moral compass that doesn’t align with yours or mine, but his desire to get out of the holler, his aspirations for upward mobility, this is the foundation for his moral compass,” Goggins says. “Money is his ticket out of this life. And how do you get out of poverty? You can play basketball. You can play football. Or you can be a criminal.”

On his own, Boyd was a force of nature. It took the sudden (yet perfect) blossoming of a relationship with his brother’s widow Ava (Joelle Carter) to humanize his ambition in Season 2. “I don’t think he ever thought being in love was in the cards for someone like him, and this relationship really rocked his world when it came into being,” says Goggins. Finally, his aspirations were joined with a tangible purpose: “I don’t think Boyd had ever been afraid of losing anything, but when you have something of real value in your life, then it sort of takes on a different meaning, and for him that thing of value was his relationship with the love of his life. But as with all things that are born out of violence, it had a lot of ups and downs.”

The final “down” came when Ava, desperate to escape what seemed like inevitable imprisonment, shot Boyd in the chest, stole the $10 million he’d just stolen, and started her run from the law. Though Raylan found Ava four years later raising a son Boyd could never know about, he made a special trip all the way out to Kentucky to tell Boyd Ava had died. It was a gift, in a strange way, to give Boyd a sense of closure and prevent him from ever interfering in the life of Ava and her son.

Such a gift could only come out of Boyd and Raylan’s own strange connection, one that began back when the two were just 19, digging coal together. Their particular relationship had its own violent ups and downs—mostly downs, given their positions on opposite sides of the law—but in last night’s finale, the pair came back to their roots. “Boyd was over the moon to see Raylan on the other side of that glass,” says Goggins. “And Raylan gave him the two things he wanted: Acknowledgement that Boyd truly loved Ava, and that they were friends.”

More than that. “We dug coal together” are the last words we’ll ever hear Boyd Crowder speak. They’re a callback to Raylan’s “Boyd and I dug coal together” line in the Justified pilot, but even on their own, they’re deep. You can feel the weight of a mountain pressing down on them, a force more powerful than enmity or friendship.

They dug coal together.