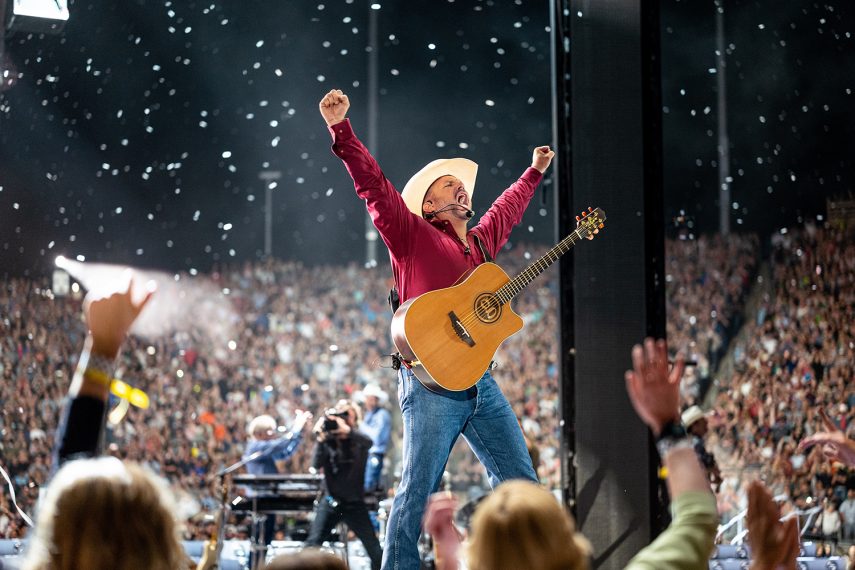

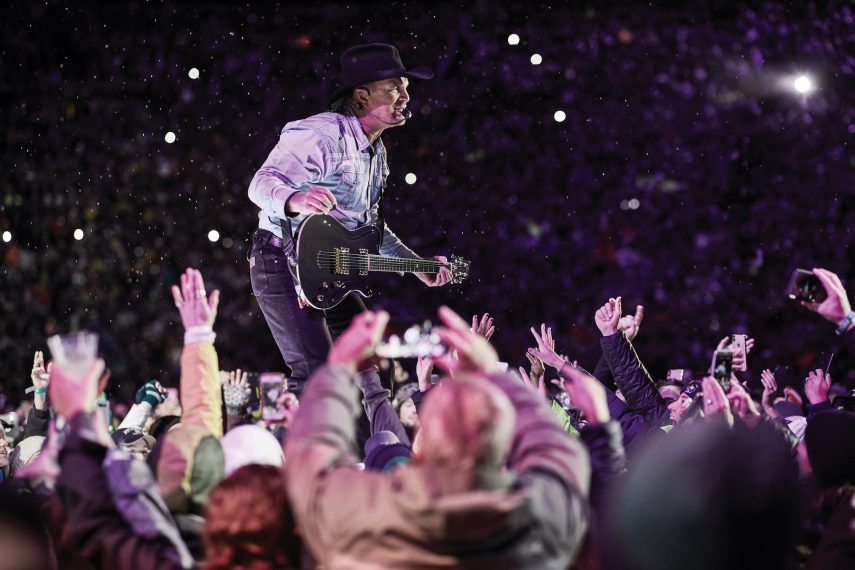

‘The Road I’m On’: Garth Brooks Previews His Very Personal A&E ‘Biography’

Q&A

He’s the best-selling solo artist of all time, who walked away from his career in 2000, for the better part of 14 years, to raise his three daughters. Of course Garth Brooks’ revealing installment of A&E’s Biography franchise, Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On, had to be a two-night event.

Highlights in December 2’s Part I include his rocky start in Nashville and the story behind the beloved hit “The Dance.” Part II, airing December 3, has the first on-camera interviews with his girls (Taylor, August and Allie), now in their 20s.

“You can imagine how your stomach cramps when you go, ‘You’re gonna talk to my children?’ ” Brooks tells TV Insider. He gives us a preview.

You get very emotional at times, like when you’re recounting your genuine fear that no one would show up for your 1997 HBO concert in Central Park. Did you anticipate that?

Garth Brooks: No. If you do an interview for a documentary, it’s always about other artists; it’s never you. Then all of a sudden you start—oh s**t, I’m gonna start getting choked up here now—remembering looking up and seeing those [million] people. And all those fears of nobody’s showing up get replaced with fears of, Oh my God, this many people showed up and now you’re scared you’re going to disappoint ‘em. And they were so perfect. It came as a shock to me, ‘cause I stand out in New York City like a sore thumb. I’m the last guy that seems to be from there. But that night, they treated me like I lived with them.

That’s like your Ireland concerts in the ‘90s. American fans may be as surprised as you were then to see just how huge you are there. What was reliving that tour like?

I get a call from a promoter over there, and I can barely understand him because his accent is so thick. But what I get out of the conversation is he says, “Three pictures hang on everybody’s wall in this country: The Pope, John F. Kennedy and Garth Brooks.” I said, “You got be kidding me!” We had no idea. He says, “Please come over and play your music.” And I thought, well, we’ll be happy to, because this guy’s sweet. We’d had a great time over here in the States; I’d never seen anything like Dublin, Ireland. It was crazy. Remember that country music is American music. It’s tellin’ American stories. It should not translate over there. But they found something in it. Maybe it’s pulling for the underdog. That’s what Ireland is: working class, strong, loving people. It was cool to get that surprise.

And what I love about this [Biography documentary] is somebody else gets to tell the story of when you came out on stage over there, how it just went through you like lightning. That’s Ty England. He was my college roommate and he’s still playing with us.

We also hear the stories behind the music. Like how the piano intro for “The Dance” was inspired by a scene in the movie The Man From Snowy River, which you and pianist Bob Wood had each seen in theaters the night before recording it.

In the 30 years we’ve been getting to play music, the guys that cut the very first session are the same guys that cut the very last one. They’re called the G-Men, there’s seven of them. We lost the bass player to cancer about four years ago. But other than that, it’s the original guys. So we were all together on “The Dance.” There’s a fun little thing that we do in studio: if somebody asks the question “What’s the intro?” then immediately everybody points to whoever said it and what’s the intro and goes, “You got it.” Because if it’s just blank, that means nothing’s been written for it and nobody wants it. ‘Cause it’s just, what do you do?

So I just sit down and play them “The Dance” [written by Tony Arata] on my guitar, and Bobby Wood says, “What’s the intro?” [Laughs] Everyone laughed and said, “It’s you.” And I’d just taken [my first wife] Sandy [Mahl] to see The Man From Snowy River. I remember that like yesterday. It was like four couples in the movie theater scattered out. Well, I had no idea until I sat down next to Bobby on that bench that he was one of those couples that night. Never saw him, never talked to him. And he goes, “I was there last night. Same movie theater.” I said, “Remember when the horses hit the snow and everything goes into slow motion?” He goes, “OK, I think I know what you want.” And that was the first take.

A&E

And this is something that people don’t understand about studio musicians. [Laughs] They only play something once and then they go to another session at two o’clock that day. So he hates to play the intro to the song because he can’t play it the way he did. Now the guy that plays on the tour band has played it 4,000 times, so he knows that intro inside and out. So Bobby always defers to David Gant. Bobby would go, “David, will you play the intro to ‘The Dance’” even though Bobby wrote it. [Laughs] it’s a beautiful piece. I can’t imagine “The Dance” without what Bobby Wood just pulled out of his heart and soul in that 20 seconds that he played.

Another incredible story is how you refused to sing the national anthem at the 1993 Super Bowl until NBC aired your video for “We Shall Be Free” (a song inspired by the L.A. Riots) before the game, as promised. How far out of the stadium did you actually get that day?

The cab came around, I put my stuff in the trunk of it and that’s when [my manager] Bob Doyle came out and said, “Get dressed. They’re gonna play the video…” I barely got out just in time to start the national anthem. I don’t know if you’re like this, but you always wonder why some things just have to come to fights. Why can’t we just do what we said we’re gonna do instead of having some kind of hidden agenda and then all of a sudden, it puts everybody in an awkward situation. I don’t want to be a troublemaker. At the same time, you got to stand up for what you do.

I think people are still fascinated by your retirement in 2000. Learning that your mother was a singer who gave up her career to raise her kids made me understand how the thought of walking away would even occur to you. You, Sandy, and your girls lay out how you navigated that time following your divorce—making sure the kids saw both parents each day. What do you hope people finally understand about your retirement?

Just as a dad to you [Laughs], let me tell you this: There’s going to be storms. There’s going to be fireworks. There’s going to be people screaming in your ear, left and right. They’re going to be calling you names. But all they’re doing is trying to distract you from what you do. You’re sailing your ship. So no matter what s**t’s going on left and right, you know where you’re going, you see your star and you just stay focused on that. The rest of the world will eventually bend to your way because it’s your life, right? So don’t let people take you off your path. So when you say, “What do you hope they understand from that?” I don’t know that they understand anything. I had to go home and raise my kids because someone else was raising them.

A&E

I wasn’t being my mom and dad to my kids. So that was my star and my ship. I had people left and right putting retirement in air quotes: “Oh he’s ‘retired,’ right?” Until finally I started to hear, “Brother, are you ever going to come out of retirement? I was too young to see you.” And you start smiling in the grocery store ‘cause they’re starting to go, “Holy s**t. This guy’s doing what he said he’d do.”

And then Steve Wynn changed everything for me out in Vegas [in 2009, with the idea of doing a residency at his Encore Theatre]. I was lucky enough to have people, casinos, everything say, “Come play us” and I’d say, “Hey man, I’m tired.” When I was sittin’ down with Steve Wynn, he said, “Tell me why you’re not playing anywhere.” And I told him about my kids [in Oklahoma]. He goes, “Oh, this is an easy deal to make.” And I looked at him and said, “Did you not hear a single word I said?” [Laughs]

A&E

He said, “Yeah. It ain’t about money.” And it caught me off-guard. He said, “This is about you getting to have the same life you had while getting to play music, but what comes first is your family life.” And I’m sitting there going, “This guy’s coming from some angle. I don’t trust him.” He said, “The first thing we’ll do is we’ll get you a plane.” I said, “Excuse me?” “The first thing we’ll do is we’ll get you a plane, so your life at home doesn’t change. You don’t miss anything, and you get to come and play music for me here.” It was a handshake deal. And so that kind of also let us know that hey, maybe there was still people out there that might be interested in our music after all these years of being gone.

My last question is a burning one I think people will have after they see Night 1. Fans who watched Ken Burns’ recent Country Music docuseries on PBS will already know the story about how in 1988, a Capitol Records exec heard you play at the Bluebird Café in Nashville shortly after passing on signing you and reconsidered. But you go into more detail here: You were slated to go on seventh that night, and the guy who various execs were there to see was supposed to go on second. When that singer/songwriter didn’t show up because he was sick, you got his slot. What happened to that guy?

His name’s Ralph Murphy. Ralph just passed away [last May]. Ralph’s in the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame as an artist/producer. Trust me, it didn’t affect him at all. He went on to have a great career in his own right. Every time I saw him, I hugged him, and it was kind of our running fun-loving thing. Me and Ralph got to work together pretty much our whole careers. Sweet man. Everybody loved Ralph.

Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On, Premiere, Monday-Tuesday, December 2-3, 9/8c, A&E

From TV Guide Magazine

How 'Countdown' Recruited Jensen Ackles to Go Full 'Die Hard'

Countdown boss Derek Haas talks creating the character around Ackles, and the cast teases the “Avengers”-like team of the crime thriller. Read the story now on TV Insider.