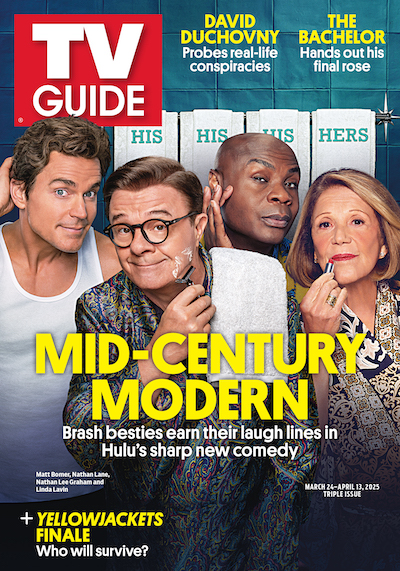

Mariana van Zeller on Real Dangers Faced While Filming ‘Trafficked: Underworlds’

Q&A

September 11, 2001. Mariana van Zeller was a Columbia University grad student when she found herself in the middle of a breaking news story. With very little time to process the unimaginable events of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S., the Portuguese journalist went boots to the ground reporting for her home country via SIC Notícias. Since then the steadfast 47-year-old built an award-winning career by fully immersing in the stories she tells, even if it puts herself at risk.

Nat Geo’s docuseries Trafficked: Underworlds with Mariana van Zeller has provided the correspondent a vehicle to dig into some of the world’s most black markets. During Season 4 alone she investigated everything from contracted killers and sextortion to hash smugglers and drug mule scams that prey on the elderly.

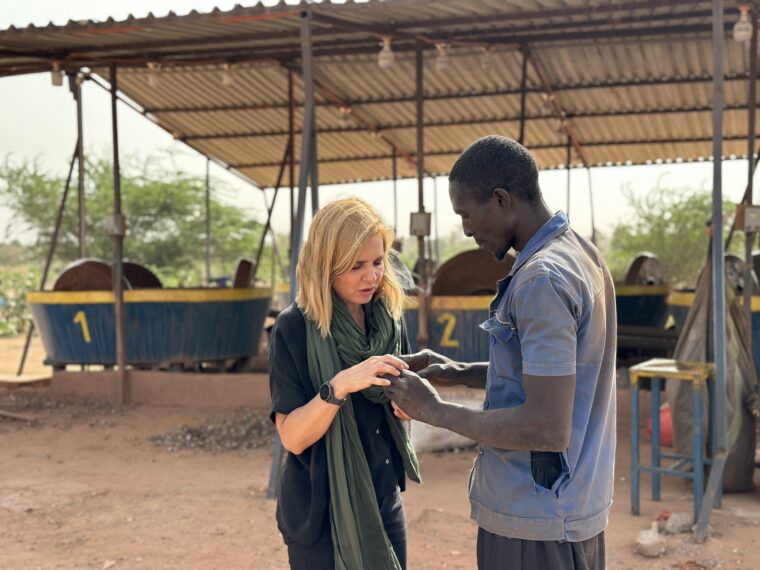

For the finale premiering March 20, van Zeller gets “trapped in her own story” while filming the episode exploring NIger’s connection between terrorism and gold. A military coup over President Mohamed Bazoum last July sent the West African country into uncertainty and chaos. Safety also became more of a concern for van Zeller and her crew. They were essentially stuck in their Agadez hotel, working feverishly to find a way out of Niger.

Here van Zeller opens up about the harrowing experience and other powerful stories told this season.

National Geographic for Disney

It’s amazing to me how you find the people within these stories that I can’t believe would even want to talk about what they’re doing. What goes into gaining their trust?

Mariana van Zeller: There is so much work that goes into gaining that access. I always say for every yes we get, we get dozens and sometimes hundreds of no’s that viewers don’t get to see. The learning I’ve had for why people talk to us is persistence and continuously just trying to get people to talk to us. I think there is a sense of ego from people who do this kind of work. Their family sometimes don’t even know they do this work. We give them the opportunity, behind a mask and disguised voice, to tell us what they do, and in many cases, what they are passionate about.

Whether it’s counterfeiting money, or making fentanyl in a lab in Mexico. There is an ego that they want to boast about. There is impunity like in Mexico. They’ve been able to operate almost with complete impunity for so many years. They don’t see a downside to talking to a trusted name like National Geographic. I think most importantly, and what I think we all have as human beings, is this need and want to be understood. With this sort of journalism, I always tell people that I’m not here to judge them. I tell them that I’m here to try to understand why they do the way they do. I think that goes a long way.

What is it like for you to tell Rodney Baldus’ story, who sits in a prison in Mozambique for drug trafficking? His daughter reaches out to you to help her dad with nowhere else to turn.

I’m trying so hard to help. You have no idea. I truly still believe in the power of journalism. What our investigation found is there is an innocent American, a former marine, possibly going to die in a prison in Mozambique. That’s why we’ve kept on this story, and I will continue on this story until justice is done in this case. It was heartbreaking. I remember receiving that direct message on Instagram from his daughter Nicole. She said that nobody was paying attention to this story and if there was anything I could do for her father. She mentions Mozambique, and I’m from Portugal. We have ties there. My dad lived in Mozambique, so I was connected.

They say he was a drug trafficker, but she was saying he was a victim of a scam. It was a one-year investigation, which made it very clear he was a victim of a scam and was innocent. It’s heartbreaking. We were there when his daughter came to visit him in prison. She hadn’t seen him in four years. She kept telling us this might be the last time she may see him. He is serving a 17-year sentence. He is 71 and very sick. He is suffering from Type 2 diabetes, and our government is not doing enough in my eyes to try to get him home. It was a different kind of episode for us. We believe there are hundreds, if not thousands of Americans who are currently in prison for the same scam. In prison with him was another American and a Canadian who had fallen for the same scam, so you can imagine how many more there are around the world. It was about a larger story, but it also became personal for me.

Mariana van Zeller interviews Ray Ray at his gambling location. (National Geographic for Disney)

There was another episode earlier in the season on hash smugglers where you go to Portugal. How was it visiting your homeland and having members of your family along for the ride?

It was great, fantastic. I couldn’t believe it. I’ve traveled with the same team since Season 1. We’re a very close-knit group. They are my family on the road. Then taking them to my actual family in my homeland was incredible. I also got to highlight a little bit of Portugal. Portugal has actually reported extensively on the drug epidemic. I was able to highlight some of the things Portugal has done right in terms of decriminalizing drugs. It was quite a privilege for me.

The finale episode getting ready to air can easily have been a season all its own with what you endured. You say in the episode that in your more than 25-year career, this was the first time where you felt trapped within your own story. How would you sum up this whole experience that viewers will see?

It was the first time I was trapped within my own story, and it was pretty scary. I’ve been someone who has covered black markets for almost 20 years and lived through so many scary moments in my life. This was especially scary. Stuck in a military coup with borders closed and airspace closed. We’re in this small town just south of the Sahara with no way out. We lost our military escort as soon as the coup happened. This is one of the most dangerous places in the world with every terrorist organization out there, kidnappers. We had no protection whatsoever. We don’t usually travel with protection, but this part of the world was just too dangerous not to. So when we lost that, with the uncertainty of it all, it was pretty scary.

You were probably thinking of your family. That must have been hard thinking about how you would get back to them.

I’m a mother. I live with the guilt of spending my time on the road. My son was in summer camp. We had this tradition where every year I would pick him up from summer camp, my husband and myself. We watch him perform in a play. He is in the performing arts camp. It’s a tradition I love. It’s my favorite day of the year. As the coup happened, I realized I had a week to get home and be there for him. The clock was ticking with threats of an invasion. I was responsible for my team as an executive producer of the show. In a lot of ways, I felt responsible for them. It was incredibly emotional. There is an incredible story that is actually not told in the documentary because it wasn’t filmed. There was a moment when we were trying everything we could to get out. I drove to the airport to see if any planes were going in or out. I was looking for answers. I met a man named Kader, who was the manager of the airport. I told him it was my son’s birthday next week. It wasn’t, but it was complicated to explain the camp situation.

The day we managed to get out where we got an evacuation company that was willing to come and get us, Kader was at the airport waiting for us. The military was there as well. They didn’t want us to leave. It was a process that lasted two hours. It was incredibly scary. Kader fought for us to leave. The moment we were going on the plane, I heard my name being called. I looked back and Kader turned to me saying, “Mariana! Mariana! Please say happy birthday to your son.” There was the guilt of leaving the country knowing I had the privilege to leave. For me, it was a difficult week. But for the people of Niger, this is an uncertain and difficult future without democracy. It was heartbreaking. The tears you see at the end are enormous relief but enormous guilt that I was abandoning the story I went to tell.

Mariana van Zeller interviews Chi Chi, a man who sells body parts illegally. (National Geographic)

Did the whole ordeal cause you to look at the job any differently? Even though your husband [Darren Foster] is in the same business, what did he think?

The thing about being a journalist, you can plan for everything. Like Mike Tyson said, plans are really nice until you get punched in the face. The punch also comes when you least expect it. We planned for everything, but not a military coup. It hasn’t slowed me down. A few weeks after we came back, I felt there was enough stability that I wanted to go back to Niger and tell the story again. We didn’t because I wasn’t allowed.

The good thing about my relationship with my husband is he is also a journalist. We met while we were in the Columbia Journalism School. We spent the first seven years of our lives as journalists traveling around the world together, and now we have a production company together. He understands why I do what I do and shares the drive of covering important stories. When I was doing a story about fentanyl in Mexico I finally got access to the lab we needed. Someone would have to pick us up in the middle of the night. We’d have to be blindfolded to take us to the lab. I called my husband to let him know this was happening. His first answer was, “Okay, great. Just make sure they film you when you are blindfolded.” I’m like, “Okay, we’re together.”

With all your travels and intense situations you are in, what keeps you centered?

That’s such a good question. I’ve never been asked that. I have a very strong relationship with everyone in the field with me. We have this routine, almost mandatory, we have to have dinner every night after a shoot or just spend some time together to digest what happened, and what we’ve been through. We call them our therapy sessions. That keeps me very grounded and keeps me sane in many ways because we can talk about everything. I feel like I need to have this human connection to keep a positive view of the world. I try to do that with the people I meet and the subjects of our stories. I would say it’s the relationships I make throughout the world that keep me grounded and positive. One of my favorite things about all these trips is no matter how far in the margins of society I travel, I still find people relatable and redeemable. That gives me a hopeful view of the world.

Trafficked: Underworlds with Mariana van Zeller, March 20, 9/8c, Nat Geo

From TV Guide Magazine

How Hulu's 'Mid-Century Modern' Is a 'Golden Girls' for Our Times

Settle in for some older and bolder laughs with the BFFs of a certain age in the new comedy starring Nathan Lane, Matt Bomer, and Nathan Lee Graham. Read the story now on TV Insider.