Why ‘CSI’ Almost Didn’t Make It to Primetime Television

After 15 years on air, there’s no doubt that CSI changed and influenced the television landscape. At the time, the show was sleek and newfangled, dark and brooding. It captured the extra-seedy underbelly of Las Vegas crime and treated fans to fascinatingly detailed slow-motion scenes of trajectory (bullets flying through the air) and anatomy (a beating heart), while also offering an inside look at the science behind forensics analysis (in very high tech-looking labs).

As CSI ends its nearly two decades run on primetime this Sunday, look back at one of TV Guide magazine’s first features below, which details how the hit show almost wasn’t aired on CBS. And read Matt Roush’s original review of CSI.

They See Dead People

It wasn’t supposed to happen. CSI, a huge success? No way.

For the first fall television season of the new millennium, network honchos dug deep into their pockets in the hope of scoring serious ratings. Big names were called in and big money was at stake. One pilot, CBS’s The Fugitive, starring Tim Daly, cost a hefty $6 million. Titanic director James Cameron delivered the lavish-looking Dark Angel and its sexy heroine, Jessica Alba, to Fox to lure young male viewers. Stars Geena Davis and Bette Midler were considered sure things for ABC and CBS. And NBC was gambling on Seinfeld’s Michael Richards.

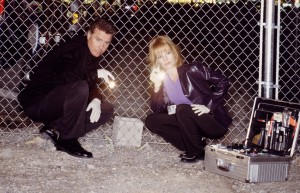

Little did those TV bosses know that the biggest new stars of 2000 would be maggots, decomposing pigs and torn fingernail fragments—and a bunch of geeks who spent too much time in the high school science lab and now believe anal swabs are cool and science is sexy. Confused? Then you’re among the few who haven’t discovered CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, starring William Petersen and Marg Helgenberger as crime analysts on the graveyard shift in Las Vegas. They are not cops. They don’t go to court and haggle with lawyers. What they do do is gather evidence, dissect body parts and examine blood samples. They see dead people—all the time.

“They’re scientists and nerds,” says Petersen. “But with DNA and this forensic stuff, they’re like cyber-cowboys. It’s Sherlock Holmes in cyberspace.”

Or Law & Order for the 21st century. But the idea that people would want to watch CSI seemed so improbable that CBS almost didn’t put it on the air. It’s got a high body count but little violence, guns but few shoot-outs; sexy leads but no sex (at least not yet). The cast? A team of investigators headed by Gil Grissom (Petersen), an entomologist (read: bug lover) who would rather watch tadpoles than bed some Vegas beauty. Rounding out the squad: fellow analysts Warrick Brown (Gary Dourdan), Nick Stokes (George Eads), Sara Sidle (Jorja Fox) and Catherine Willows (Helgenberger), a single mom and—in a nod to the seedier side of Sin City—an ex-stripper.

What’s more, creator Anthony Zuiker had never written a TV script. In fact, four years ago he was making $8 an hour operating a tram at Vegas’s Mirage Hotel. To hone his material, he rode with real crime-scene analysts and scoured the Internet and libraries for information about forensics. In other words, he winged it. As CBS president Leslie Moonves says, CSI “was not a slam dunk.”

It may have helped that there was one big gun attached to the project: producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who has made such ear-busting, macho megamovies as Top Gun and Armageddon. “We definitely were the underdog,” says Bruckheimer. “In a way, it was a great position to be in.”

Even as CBS was poised to announce its fall schedule, CSI was hanging by a hangnail. Says Helgenberger, “The question CBS was asking was, ‘Is it going to fit into our demographic?’”

And then something amazing happened. Folks at CBS research reported that CSI’s pilot was doing well with test audiences. In particular, women were loving it, which was strange for a crime drama. CSI got the green light, and has been No. 1 in its time slot (save for a special Friday airing of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire last month), far outperforming its much-hyped Friday-night CBS partner, The Fugitive.

“Men like the cop stuff. Women like the puzzles,” explains Moonves. And everybody likes Vegas, Zuiker believes. “It’s a mecca for a bunch of forensics stories,” he says. “Here’s Lake Mead—floaters, right? Here’s the desert—mob hit gone wrong. Here’s the mountains—dead men hiking. Here’s off the Strip—quadruple murder. It’s all here.”

But it probably wouldn’t have happened without Petersen, best known for the cop features To Live and Die in L.A. and Manhunter. For a decade, Moonves had been wooing him for a TV series. “He’s the type of TV star women dig and men want to hang out with,” says Moonves. But no project ever seemed right.

“Yeah, he had a lawyer show this year that he wanted me to do,” says Petersen. “I could stand in a courtroom and do closing arguments and make people cry. And I’m like, ‘Shoot me now.’ I didn’t want to be in a hospital, either. Or be married or be a single father or divorced. I wanted to be a cowboy, but in a different way.”

He got his wish. If CSI is like anything it’s like an old Western, where the good guy always gets the bad guy. Vegas adds a bit of flash, just as South Beach did for Miami Vice, but there’s a grittier feel here. “CSI is shot like a feature film,” says coexecutive producer Sam Strangis. “The lighting is designed to reflect the mood and tone of the show.” At its heart, the series is about process, with a little flash and lots of extreme close-ups.

He got his wish. If CSI is like anything it’s like an old Western, where the good guy always gets the bad guy. Vegas adds a bit of flash, just as South Beach did for Miami Vice, but there’s a grittier feel here. “CSI is shot like a feature film,” says coexecutive producer Sam Strangis. “The lighting is designed to reflect the mood and tone of the show.” At its heart, the series is about process, with a little flash and lots of extreme close-ups.

“If you’ve never seen the show you’d think, ‘Well, it’s microscopes and hair fibers and blood and DNA, and how could that possibly be fun?’” says Zuiker. “The fact is, it is fun.”

Perhaps, except all those dead bodies remind us that this stuff is inspired by real crimes. Whether he’s right or not, Zuiker believes that “we’re making this world a safer place. Criminals will watch this and go, ‘I don’t think I can get away with that’ because we solve some pretty hairy stuff. You can’t just shoot somebody and get away, because we’re going to get you.”

Petersen agrees. “These are the guys over the next 20 years that are going to redefine our criminal justice system,” he says. “They’re going to decide who goes to jail and who doesn’t.”

True Crime

Daniel Holstein and Yolanda McClary see dead people, too. Unfortunately, they’re real.

How do you spot a real crime-scene investigator? Similar to the way you spot one on CSI. “We’re the ones standing over dead people, three inches away, playing with maggots,” says Daniel Holstein, who, with fellow Las Vegas analyst Yolanda McClary, helps the folks at CSI get their facts straight. Before writing the pilot, creator Anthony Zuiker rode shifts with McClary. Now CSI’s writers e-mail Holstein to check their science and sniff out new stories.

So, does CSI get it right? “We don’t throw bodies off roofs to see if they were pushed or fell or jumped,” says Holstein, 36, who has a degree in biochemical criminology from the University of Nevada Las Vegas. “But it was cool when they did it [on the show].”

“They do their homework well,” says McClary, 37, an ex-secretary for cops who took a class in crime-scene investigation and “fell in love with it.”

The two do have their differences: She carries a gun. He does not. He loves maggots and blood. She does not. He’s had to tackle someone to keep evidence from being destroyed. She has not. (“I prefer mace,” she says.) But their job is the same: “Everything around you is trying to tell you something and you’ve got to be able to see that,” says McClary, who has worked nearly 3,000 calls in six years. “Detectives interrogate people,” says Holstein. “We interrogate the evidence.”

Sometimes, what they see is almost unbearable. A few weeks ago McClary was investigating the death of an infant when the father came home unaware of what had happened. “I have his baby in the other room,” she says. “Your stomach turns, your skin crawls, and tears well up in your eyes. At first I thought, ‘Is this something I want to do?’ But it’s about catching the bad guy. Telling the truth.”