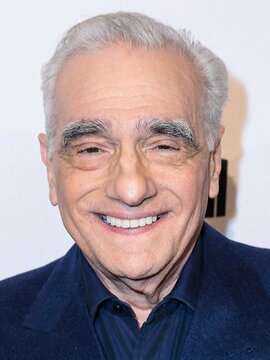

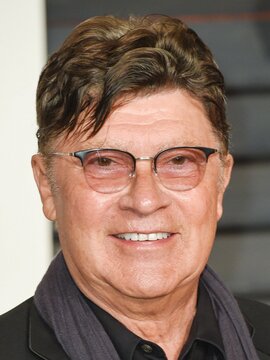

‘Mr. Scorsese’ Director Reflects on Martin Scorsese Acknowledging His ‘Dark Side’ & More

Exclusive

Father Scorsese? Strange as it may now seem, the young, badly asthmatic kid from New York who became one of the most acclaimed filmmakers of the last 50 years strongly considered the priesthood when he was a kid. That is, until the early days of rock ‘n’ roll, the lure of the opposite sex, and a world he discovered in movie houses gave him a different calling.

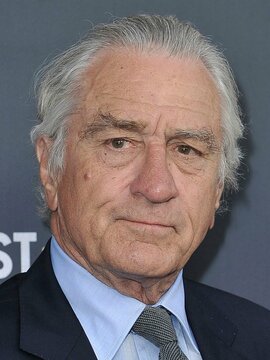

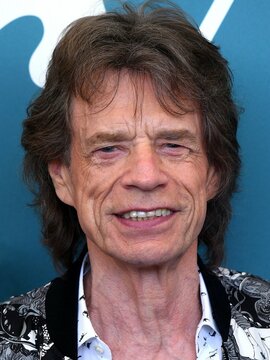

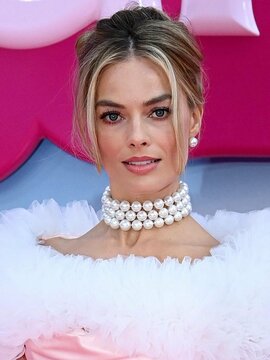

“One of Martin Scorsese‘s strengths is his willingness to recognize the conflicting emotional currents in himself,” says director Rebecca Miller, whose five-part docuseries, Mr. Scorsese, shows the journey of one of history’s essential filmmakers. Steven Spielberg, Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, Mick Jagger and many others offer comments, but it’s the 82-year-old Scorsese himself who most candidly relates the portrait of determination and failure, toughness and tenderness behind the man who made Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and other classics.

“Acknowledging his own dark side enables him to empathize with his characters,” Miller adds. “We who watch these imperfect characters treated with compassion by the filmmaker can perhaps begin to have mercy on ourselves.”

Miller spoke to TV Insider about the man and his movies.

After all the hours you spent in these interviews and in prior preparation, is there one main thing that truly surprised you about Martin Scorsese?

Rebecca Miller: I think I was most surprised by how many times he failed and had to dust himself off and start again. As a young man he had to keep hurling himself against the wall until he finally broke through, and then, even when he had made great films, there were tremendous setbacks. Each time, he needed to reinvent himself as a filmmaker.

Do you remember your impression of him the first time you met him?

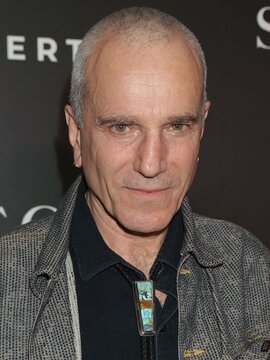

The first time I really encountered Marty, I think, was on the set of Gangs of New York [starring Miller’s husband, Daniel Day Lewis] and he was expressing some alarm or anticipation of the big battle scene in the snow, and he was so filled with uncertainty and excitement, and he just seemed like a very young man to me. And I thought, my God, here’s this genius. And he’s absolutely not sure that this is the right way to do it. He really was like a young person; that, I think, is part of his secret, honestly, that perennial youth.

In 1969 and 1970, during that era, he read the novels of both The Last Temptation of Christ and Gangs of New York. So, he’s in his late 20s. He hasn’t made Mean Streets yet. What do you see in that version of Martin Scorsese that would lead to those projects down the road?

I think it’s very interesting, how those two books took root in him so early, and just kept growing and growing inside of him like a big tree. But then sometimes you either don’t yet have the wherewithal in your technique or there’s no way of doing it practically. After all, it’s an expensive medium.

Also, he has, many times, ridden an obsession long-term and nurtured it and allowed it to grow. But the truth is he’s not somebody who’s then just satisfied and thinks, “OK, I’m done.” Each film, in a way, is evidence of where he was at that moment. When you’re trying to do a portrait, they’re his art. It’s there. But then he’s like, “I need to go deeper still.” There’s that feeling of never being done.

Is there a character in his films that you think he sees himself in the most?

Absolutely, between Johnny Boy [in Mean Streets], Kichijirō [the fisherman seeking redemption after renouncing his faith in Silence], so many of his characters. You know, Jake LaMotta [from Raging Bull] — he’s put so much of himself into so many of these characters but it’s far from anything like pure autobiography.

Let’s talk about Kichijirō from Silence. What do you see is his spiritual connection to that character?

There’s an identification, perhaps, with the sinner, or the one who comes up short from perfection. And yet he tries again. And that’s so moving to me, that that’s how he identifies.

Is it surprising to you that he’s still friends with these kids from his tough neighborhood growing up after all these years?

Not really. I would say it’s accurate that you can find the nerve endings of all his work in the neighborhood. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to dive so deeply into the family and into the neighborhood. The church is across the street from the [local] social club. In these apparently opposite worlds, this child has to integrate them into himself. And that’s really the story of his work.

Then we have the other side of it; he walks into St. Patrick’s Cathedral and says, “Suddenly, I walked into this beautiful place, and it had serenity, it had ritual, and I was part of the ritual.” What do you see as the link between his filmmaking and faith, these two beautiful, misunderstood passions?

Honestly, I think that’s why I made the film. The original impulse was, I had an instinct that the filmmaking and the faith were somehow connected. I didn’t really understand how. I didn’t really get it yet, but I was very intrigued and, in a sense, when you watch the film, that’s what you’re getting. That sense of, if you have talent, it’s a gift, and you harvest the gift. But his outlook throughout is quite spiritual, like, even in the darkest moments and even in the darkest films, he’s looking at it through a lens that was created all those years ago in St. Patrick’s. You kind of feel how those two things go together.

If you had to set up a Scorsese double feature that showed the range of who he is, which two films would you pick?

That is such a difficult question — I want to include so many films! I will go for two opposites: Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and The Wolf of Wall Street. Alice is about a woman forced to take control of her own life; it is a wonderful portrait of a person reinventing themselves. It’s also a hilarious and tender portrayal of a mother-son relationship. Wolf of Wall Street is a tour de force of cinematography and editing, a funny and dark portrait of American greed run amuck. It is a very male movie. Both films are truthful portraits of human beings.

There was all that great stuff with him living with Robbie Robertson and nearly dying from drugs. And he’d had bad asthma as a kid; it seemed to build this idea that he was always going to do what he wanted to do, period. But how has he maintained that toughness?

I think people who are very sick as children become quite tough, because a child who has to fight for every breath, that fight is a fight for your life and when you’re ill like that and you survive it. And I have to say, I never thought of this, but I can really identify because I had lupus when I was a kid and I was very sick, and there’s something about being really sick and coming out of it. And I think I understood that. And speaking to him, there was a kind of recognition, and I think that’s the toughness; it started back then.

He was cooped up, and he had to watch movies, and he had to go into the movie theaters [where there was air conditioning], but also had this identity as a child who has to fight for their life. That’s somebody who gets used to fighting. And there’s that funny moment when Spike Lee says, “Thank God for asthma!”

Mr. Scorsese, Premiere, Friday, October 17, Apple TV