Gripped in the giant hand of "King Kong" (1933) in a simulated New York City on the RKO backlot, Fay Wray emitted screams of terror that reverberated throughout a nation stunned by the Great Depression. By the time the Canadian native was cast in the role of Ann Darrow, human inamorata of the eighth Wonder of the World, Wray was already a successful Hollywood actress whose previous leading men included William Powell, Gary Cooper and Fredric March. Although she had retired in 1942, the death of her second husband, screenwriter Robert Riskin, drove the actress back to work in character parts, including a comedic turn as an affluent hypochondriac in "Tammy and the Bachelor" (1957). An iconic figure in cult film circles, Wray eventually turned her back on performing to enjoy frequent public appearances as herself.

Living well into her nineties, Wray turned down the offer to contribute a cameo appearance to director Peter Jackson's 2005 remake of "King Kong" shortly before her death from natural causes in late 2004. Though she appeared in all manner of movies, from dramas and comedies to horror films and the early Westerns in which she had performed her own stunts, Fay Wray would be remembered principally for her most famous role, as well as for the honor of being cinema's first bona fide scream queen.

Vina Fay Wray was born on Sept. 15, 1907, in Cardston, Alberta, Canada. At the time, she was the youngest of the four children of rancher and saw mill proprietor Joseph Herber Wray and his wife, Elvina Marguerite Jones, a former school teacher. The harsh Canadian winters eventually drove Vina Wray to the brink of a nervous breakdown; while she recovered in a sanitarium, her children were farmed out to local families. Immigrating to the United States after World War I, the Wrays settled in Salt Lake City, UT, where Joseph Wray worked as a night watchman.

As a young girl, Wray enjoyed trips to the local movie theater and made her stage debut as Mrs. Claus in a school Christmas pageant. Wray's parents separated shortly after the family relocated again, to Lark, UT, where her father had found work in a copper mine. By this time, the family had grown with the addition of two more children.

When she was 12 years old, Wray took part in a Salt Lake City newspaper subscription drive whose grand prize was a starring role in a moving picture. When her film debut turned out to be no more than a single scene photographed as part of a publicity stunt, Wray accepted a menial job with the same newspaper, stuffing envelopes. When she was 14 years old, Wray was sent with her older sister Willow to the more forgiving climate of Los Angeles, where she lived with a succession of friends and enrolled as a student, first at the Thirtieth Street Junior High School and eventually Hollywood High School.

At the age of 15, Wray lodged her foot in the door of the burgeoning film industry with bits in two-reelers before winning a starring role in Bud Barsky's "The Coast Patrol" (1925). Given a six-month contract with Hal Roach Studios, Wray appeared in a number of silent comedies, earning $60 a week, and sometimes carpooling to the studio with future Academy Award winner Janet Gaynor.

Lured away to Universal Studios with the promise of more work and a $15 a week pay increase, Wray appeared in a string of Westerns, often performing her own stunts on horseback. She was the leading lady of cowboy actor Hoot Gibson in "The Man in the Saddle" (1926) and appeared in several films by director William Wyler. Along with Joan Crawford, Mary Astor and Delores Del Rio, Wray was one of the WAMPAS (Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers) Baby Stars of 1926. On loan to Paramount, she was paired with rising star Gary Cooper in William Wellman's "The Legion of the Condemned" (1928).

Wray abdicated her spot at Universal to work with auteur Erich von Stroheim on "The Wedding March" (1928). After nine months of filming, the ambitious project was taken away from its creator (its running time split down the middle and released as two separate films) by Paramount, who subsequently claimed Wray's contract.

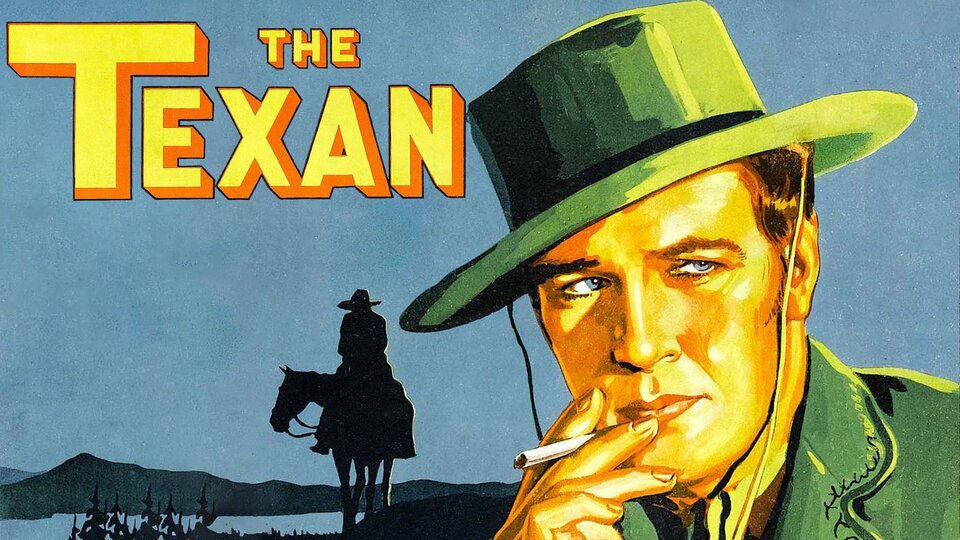

As a Paramount employee, Wray survived Hollywood's transition to sound films that had finished many a career from the silent epoch. For director Merian C. Cooper, she appeared in "The Four Feathers" (1929), alongside William Powell and Richard Arlen, while reuniting with Gary Cooper for "The Texan" and "The First Kiss" (1928). After the stock market crash of 1929, a cash-strapped Paramount began to loan out its contract players to other studios.

For Columbia, Wray played the leading lady to Jack Holt in "Dirigible" (1931), an early film by director Frank Capra, and for the Samuel Goldwyn Company she was paired with Ronald Colman in the Sahara-set "The Unholy Garden" (1931). Married in 1928 to John Monk Saunders, Wray lost the lead role in William Dieterle's "The Last Flight" (1931), based on Saunders' novel Single Lady; she made her Broadway debut in a short-lived musical adaptation of the book in the fall of that year alongside a young British actor named Archie Leach who would find success in Hollywood as Cary Grant.

Back in Hollywood, the diminutive and dimpled actress was put to good use as a prototypal scream queen in a number of early horror thrillers - among them the early Technicolor spookshows "Doctor X" (1932) and "Mystery of the Wax Museum" (1933), both directed by Michael Curtiz, and Frank Strayer's Poverty Row cheapie "The Vampire Bat" (1933).

The apotheosis of Wray's tenure as a damsel-in-distress came with her casting in Merian C. Cooper's "King Kong" (1933), directed in tandem with Ernest B. Schoedsack at RKO. The quintessential monster-on-the-loose story benefited greatly from the pioneering stop-motion special effects of Willis O'Brien, allowing a giant ape to run amuck on an uncharted South Seas atoll and later in Depression era New York City and to come to his sad end after climbing - with Fay Wray clutched in one massive hairy mitt - to the top of the Empire State Building, then still under construction. Her blood curdling screams as the obsessed ape took possession of her would become one of cinema's most iconic scenes in the history of the medium.

Though Wray worked on "King Kong" for a total of 10 weeks, production tied her up for 10 full months, from which she collected a paycheck of only $10,000. During the making of the film, Cooper and Schoedsack produced a modestly-priced island thriller, which Schoedsack co-directed with Irving Pichel. Based on the story by Richard Connell, "The Most Dangerous Game" (1932) utilized standing jungle sets from "King Kong" and some of the film's supporting actors.

Cast opposite Joel McCrae as a pair of island castaways hunted by a Russian nobleman with a taste for human trophies, Wray did less screaming than in "King Kong" and revealed a markedly grittier and more resourceful side. Though her acting career would continue for several decades, the cultural impact of her career rested squarely with two performances. By 1933, she had also become a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Signing a non-exclusive contract with Columbia, Wray appeared around town in a flurry of features through the next few years. At Paramount, she played an atypical bad girl role in "One Sunday Afternoon" (1933), again opposite Gary Cooper. At Fox, she was paired with Spencer Tracy in John G. Blystone's "Shanghai Madness" (1933), and at Universal she played a young actress who passes herself off as "The Countess of Monte Cristo" (1934).

At Columbia, she fled from voodoo practitioners in "Black Moon" (1934) and at RKO she switched places with Miriam Hopkins to play at being "The Richest Girl in the World" (1934). In England, she appeared in "Alias Bulldog Drummond" (1935) with Ralph Richardson and "The Clairvoyant" (1935), starring Claude Rains, but lost out back home on a coveted role in Frank Capra's classic "Lost Horizon" (1937). In 1939, Wray divorced Saunders, whose alcoholism had spiraled towards increasing mental instability. He committed suicide by hanging in Florida in 1940. In 1942, Wray married legendary screenwriter Robert Riskin and effectively retired from show business.

Crippled by a stroke in 1950, Riskin died in 1955. During this time, Wray appeared in a few films in supporting roles before resuming her career as a regular on the ABC situation comedy "The Pride of the Family" (1954-55), which also provided two seasons of work for a 15-year-old Natalie Wood. In Vincente Minnelli's "The Cobweb" (1955), Wray enjoyed the small but pivotal role of the wife of Charles Boyer's disgraced psychiatrist, and she reteamed with her fellow WAMPAS star Joan Crawford for the campy "Queen Bee" (1955).

In "Hell on Frisco Bay" (1956), Wray's testimony saved the reputation and neck of star-producer Alan Ladd and in "Tammy and the Bachelor" (1957), she was the stick-in-the-mud mother of leading man Leslie Nielson. Working mainly in television through the end of the decade, Wray capped her career with an appearance in a 1965 episode of the long-running courtroom drama "Perry Mason" (CBS, 1957-1966), though she again came out of retirement for the fact-based telefilm "Gideon's Trumpet" (1980), starring Henry Fonda.

In 1970, Wray married one of the doctors who had attended her late husband, Riskin, and retreated into family life, world travel and occasional public appearances, such as the 70th Academy Awards Presentation. An iconic figure in cult film circles, Wray enjoyed frequent public appearances as herself. In 1989, she published her memoirs, which bore the wry title On the Other Hand. Filmmaker Peter Jackson attempted to lure the nonagenarian out of retirement one last time to contribute a cameo to his proposed big budget remake of "King Kong" (2005), but Wray demurred.

Following her death at age 96 from natural causes in Manhattan on Aug. 8, 2004, the lights at the top of the Empire State Building were dimmed in her honor. Wray was buried at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, not far from the former citrus groves in which she had strolled as a young woman and the studios for which she had made for herself a life in pictures.

By Richard Harland Smith