‘War & Peace’ Brings Gorgeous Russian Grandeur to TV (and a Dash of Incest)

Everyone knows three things about 19th-century novelist Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace: It’s Russian, it’s old and it’s long. The average English translation fills 1,440 pages. It has 365 chapters and a plot that follows five aristocratic families throughout 15 years of Napoleon’s devastating (if doomed) attempt to conquer Eastern Europe and Moscow in the early 1800s. Which is why it’s remarkable that—in an era of GIF-length attention spans drawn to galaxies far, far away—War and Peace remains undeniably popular. Its 2007 translation is still an Amazon bestseller. A recent New York Times survey revealed it to be one of the most read books by subway riders. In December, hundreds of Russian glitterati teamed up for a 60-hour marathon recitation of the text that was live-streamed worldwide. And now the BBC, with U.S. producers the Weinstein Company, has jumped on the horse and buggy with a lavish, six-hour adaptation that will air simultaneously on Lifetime, History and A&E over four weeks.

“The series is about love, hate, jealousy, forgiveness—all things we experience in any country, in any period,” says British actor James Norton, who plays handsome Andrei Bolkonsky, the brooding soldier at the center of the epic. “Tolstoy wrote people and relationships so beautifully, we can always relate to them.”

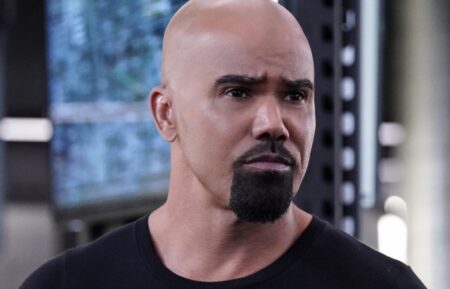

Paul Dano

Golden Globe nominee Paul Dano (Love & Mercy) joins Norton as Pierre Bezukhov, a bighearted libertine whose faintly Cro-Magnon looks and progressive opinions are about as welcome among high society as a bug in soup—until he unexpectedly inherits a fortune. “Pierre’s like the guy in high school who is dorky but kind of rad at the same time,” Dano says, “because he’s curious, passionate and not bound by what others say.”

RELATED: War and Peace: Trimming Tolstoy’s Epic Tale for a Modern Age

Andrei, Pierre’s closest friend, is just the opposite: disillusioned and knotted with existential angst. Countess Natasha Rostova (Downton Abbey’s Lily James) is the plucky heroine who falls for both men—and Pierre’s slimy cousin, Anatole Kuragin (Callum Turner). “Natasha has a soaring spirit,” James says. “Everyone wants to be around her because, as Andrei says, ‘You seem to have the key to happiness.’ But that also means she has the key to grief and can sink to great depths. She lives in extremes.”

The rest of the star-studded cast includes Stephen Rea as Anatole’s scheming dad, Vassily; Oscar winner Jim Broadbent as Andrei’s cruel, demanding father, Nikolai; Gillian Anderson as moneyed hostess and cunning matchmaker Anna Pavlovna; and Brian Cox as the beleaguered head of Russia’s army, General Kutuzov.

“It’s magical,” James gushes of the immense production. “The grandeur was like nothing I’d witnessed. I’d thought I’d seen it all on Downton, but I hadn’t.” The series employed over 100 cast members, 500 extras and 550 crew members. (It took 1,200 hours to edit.) The actors comprising the five main families alone required over 400 different costumes, 85 percent of which were hand-sewn. Thousands of other period getups were rented from across Europe, while 600 Russian and French military uniforms were re-created from scratch in Poland. The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg even allowed the art department to make copies of several of its prized portraits to adorn the characters’ estates—as long as the fakes were destroyed as soon as filming ended.

And that was the easy stuff. “In Britain, we take for granted that we have all these old, stately homes where we can film our period pieces,” says the series’ English director, Tom Harper. “But that’s not true of Russia, where they’ve had two World Wars and a communist revolution. All the rich estates were seized and turned into institutions. That made finding locations really, really hard. Particularly because there are so many characters on the show, and they’ve all got about three houses each. We ended up filming in three different countries.” The interiors of Latvia’s baroque Runda-le Palace doubled for several Russian mansions. With a little pruning, the main street of Vilnius Old Town, Lithuania, became Tolstoy’s Moscow, while nearby farmland was landscaped into a muddy battleground for the show’s massive combat sequences, which featured full mounted armies.

Lily James

“Riding across the battlefield with 300 extras in their greatcoats while brandishing a saber above your head and shouting ‘Charge!’ can be like heaven,” Norton says. Not so divine? Doing so with a gigantic Russian army shako cap. “I had a hat issue,” he admits with a laugh. “They just didn’t stay on. When you jump up and down during a big brave moment and your flippin’ hat falls off, it’s the most unheroic, comedic thing that can happen.”

On the other hand, it was still preferable to filming one of the many grand balls. “On the battlefield, you can get away with shouting and tripping,” Norton says. “In the ballroom scenes, you had to do specifically timed pieces of laughing and dancing and music. It’s so much pressure!” The ball where Natasha and Andrei fall in love—one of the novel’s most celebrated moments—was shot at Catherine Palace (once a summer hideaway for Russian tsars) outside St. Petersburg. “We filmed in a room where balls like that would’ve really happened,” James says. “It was covered in gold from floor to ceiling. We waltzed to a real Russian orchestra, and when the final note played, the reverb in the room seemed to go on for a lifetime. It made my hair stand on end.”

Screenwriter Andrew Davies, the Welsh scribe responsible for TV versions of literary behemoths Middlemarch and Bleak House, reduced War and Peace to six hours by cutting out what he calls the “baggy” parts. Yet he’s also the writer famous for having Colin Firth take a sexy midday swim wearing a white blouse in the 1995 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (an event not in Jane Austen’s original), so he naturally added some naughty bits to Tolstoy’s story—like giving the incestuous relationship between Anatole and his sister (which some think is hinted at in the novel) the full bedside treatment—causing some grimaces in Britain, where the series is already airing.

Never fear, though: Andrei (who has been called the Russian Mr. Darcy) won’t be entering any wet-blouse contests. Primarily, it was just too cold—he and Natasha do most of their frolicking through the Russian woods while knee-deep in snow. Norton recalls temperatures during the filming of those scenes dropping to negative-25 degrees. “We got an email warning of hypothermia and I’m a huge hypochondriac,” James adds. “I was so nervous. I kept wiggling my toes so they wouldn’t come off.”

Altering the story too much wouldn’t be right anyway. “While working in Russia, we saw how much the book meant to people,” Norton says. “We went to a production of The Cherry Orchard, and the director, a Russian theater legend, wanted to meet the man playing Andrei. He asked me, in Russian, how old I was. When I told him [Norton is 31], he replied, ‘No man under 40 has ever played Andrei because his circles of contemplation are so complex that no man should ever do it unless he is ready.’ It was scary! Then he looked at me and said in English, ‘Good luck.’ There was a real sense he was saying, ‘Don’t mess it up!’”

War & Peace, Miniseries premiere, Monday, Jan. 18, 9/8c, A&E, Lifetime and History Channel